A Consideration of Freemasonry’s Democratization of the Mysteries

According to certain traditions, the ancient Greek Mystery initiations at the Sanctuary at Eleusis began with a declaration to those not prepared for initiation: “Be gone!” The Mysteries at the Greek town of Eleusis which took place for at least a millennium until 329 BCE, were rites centered around the myth of the abduction of Persephone, the daughter of the fertility goddess Demeter, and her abduction by Hades, the lord of the underworld. These rites were open to the public, but were not available to the profane viz., those unprepared for initiation. The requisite preparations were few, but important: (1) Initiates must have never committed homicide. (3) The sacrifice of a piglet to Demeter was required. (4) A ritual purification in the river Illisos had to be undergone after the sacrifice. These four requirements having been met, anyone— man, woman, or youth— could be initiated. The Roman orator and statesman Cicero remarked of the Eleusinian Mysteries,

For it appears to me that among the many exceptional and divine things your Athens has produced and contributed to human life, nothing is better than those mysteries. For by means of them we have transformed from a rough and savage way of life to the state of humanity, and have been civilized. Just as they are called initiations, so in actual fact we have learned from them the fundamentals of life, and have grasped the basis not only for living with joy but also for dying with a better hope.

Ike Baker

Author of A Formless Fire: Rediscovering the Magical Traditions of the West

Ike Baker is the author of A Formless Fire: Rediscovering the Magical Traditions of the West. He hosts the ARCANVM YouTube channel and podcast, producing documentary-style presentations on esoteric traditions and facilitating conversations with the foremost scholars, practitioners, and researchers in the fields of philosophy, occulture, and the esoteric traditions of the west. He is also an instructor at the Institute for Hermetic Studies, as well as an initiate and practitioner in western initiatic lineages of Freemasonry, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Rosicrucianism, and Martinism.

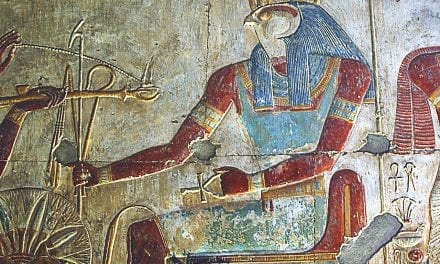

This democratization of the Mysteries was characteristic of early Greek culture. However, it was not the historical norm among initiatory institutions. The rites of ancient Egypt were closed to all but the priest-class. The rites of ancient Samothrace were open to the public for participation and worship, but certain centers within the complex were closed to all except initiates. The initiatory cult of Mithras was closed to all but soldiers of the Roman legion. Indeed, initiation into the Mysteries of the ancient world were reserved for a select few. Even those initiated in the egalitarian Eleusinian Mysteries were forbidden from mentioning their proceedings to those who were as yet uninitiated in them. However, becoming initiated at Eleusis did not confer any special rank as a priest or priestess. Neither did it mean one was free to initiate others into the tradition, whether that be on their own or at the actual nine-day ceremony at Eleusis. It was more like the rites of Christian sacraments— the mass of the Eucharist, in particular. It was a divine service offered to the public who had qualified to receive it. It offered a type of religious experience to bolster their activities of daily living and perhaps orient their thoughts toward higher aims than the merely mundane. However, there must be some sort of requirement otherwise the Mysteries or which each initiatory body claims custodianship are rendered meaningless.

From its earliest historical periods Freemasonry has been an initiatory tradition with certain specific requirements of all candidates to membership viz., some form of theism, good moral character, and being a man. However, those requirements have been subject to serious debate and change over the ensuing centuries. Despite these requirements Freemasonry, highly influenced by Enlightenment-era Protestantism, embodied a progressive, egalitarian spirit approximating a kind of proto-globalism. In any event, entire offshoot organizations have been spawned from the early modern period of Freemasonic endeavor in Europe and, while extending from the trunk of Freemasonic tradition, have evolved to differ from Freemasonry in significant ways. The beginning of this period becomes historically visible in the 18th century.

This was a period of rapid and continual innovation in the Freemasonic tradition, as well as a certain amount of competition between different strains of Freemasonry— each claiming to represent a sort of Masonic orthodoxy and vying for recognition of their authenticity. This was perhaps most evident in the conflict between the “Ancient” versus “Modern” distinctions during the early Grand Lodge period in England (1717–1813). Others however, continued to innovate and expand the tradition by the creation of various Masonic and Masonic-associated degrees and Orders.

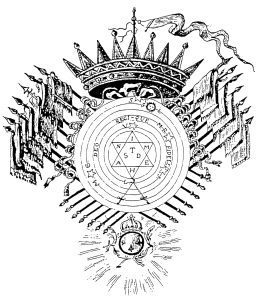

Early on we have the haute-grade or “high” Masonic degrees of Étienne Morin (c.1717–1771) in his Order of the Royal Secret, which conferred twenty-five degrees, considered ancient Scottish Freemasonic rites. This degree system would go on to influence the development of the Scottish Rite. Around the same time, Martinez de Pasqually (c.1727–1774) was traveling around southern France chartering lodges known as Le Juges Ecossai (Scottish Judges) a Masonic chapter called Le Temple Cohen (The Cohen Temple or Temple of the Priest). This would later evolve into the radical Ordre des Chevaliers Maçons Élus Coëns de l’Univers (Order of Knight-Masons Elect Priests of the Universe) or Élus Coëns. A student of Pasqually, Jean-Baptiste Willermoz (1730–1824), would found the Rite Écossais Rectifié (Rectified Scottish Rite) and its inner order the Chevaliers Bienfaisants de la Cité Sainte (Knights Beneficent of the Holy City) or CBCS. An even more enigmatic figure, Count Alessandro Cagliostro (1743–1795)—born Giuseppe Balsamo—would go on to form an Egyptian Rite of Freemasonry, influencing the development of several Masonic and formerly-Masonic bodies in the ensuing century—perhaps most notably the controversial Ancient and Primitive Rite of Memphis and Misraim. The notable English Freemason John Yarker (1833–1913) also had ties to the Rite of Memphis-Misraim, as well as several other innovative Masonic Orders.

The formation of the Ordo Templi Orientis (Order of the Temple of the East) by German Freemasons Theodor Reuss (1855–1923) and Carl Kellner (1851–1905) is another significant example of this type of innovation. The OTO was formed to be a Masonic College which taught specific tantric and yogic techniques and philosophies from ultimately Eastern sources.

Even more influential on the culture of esoteric Freemasonry and occultism in general was the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Founded in London in 1888 by the English Freemasons William Wynn Westcott (1848–1925), Samuel Liddell Mathers (1854–1918), and William Robert Woodman (1828–1891), the Golden Dawn was an initiatory system focused on ceremonial magic (theurgy in particular) and grew out of the Rosicrucian Masonic tradition which was exceedingly popular at that time period. The Golden Dawn was directly influenced by Rosicrucian Masonic orders such as the Societas Rosicrucian in Anglia (Rosicrucian Society in England)— SRIA— and the German Orden Gulden Rozenkreutz (Order of the Golden and Rosy Cross)— OGR. The OGR was not technically Masonic but required its candidates for initiate to be Master Masons. At the time of the inception of the Golden Dawn all of its founders were high ranking members of the SRIA. The Golden Dawn was itself an outer court, concealing a Rosicrucian Inner Order of Adepts referred to as the Ordo Rosæ Rubeæ et Aureæ Crucis (Order of the Ruby Rose and Cross of Gold).

Finally, we harken back to the rite of Pasqually. Another of his students was the influential Louis Claude de Saint-Martin (1743–1803), who wrote several philosophical and mystical treatises under the pen-name le Philosophe Inconnu (the Unknown Philosopher). It is debated as to whether or not Saint-Martin ever started a formal order after breaking away from the Élus Coëns, however in 1886 a French physician named Gerard Enausse (1865–1916), also known by the name Papus, formed the Ordre Martiniste (Martinist Order) alongside historian Augustin Chaboseau (1868–1946). Two years later, Papus would take part in the founding of the Ordre Kabbalistique de la Rose-Croix (Kabbalistic Order of the Rose Cross)—OKR+C— with novelist Joséphin Péladan (1858–1918) and the poet Stanislas de Guaita (1861–1897).

There are many more instances we could speak of, but this is a blog post after all. What these organizations had in common was that they served as expressions of what their founding members interpreted as the esoteric or “inner” teachings of Freemasonry. The consequence of these many lineages and interpretations of esoteric Freemasonry, encompassing mystical and magical teachings from the western and eastern spiritual traditions of antiquity was the democratization of the Mysteries. Whereas in preceding eras initiation into Mystery traditions was reserved for those meeting qualifications established by hieratic authorities and performed by those who had devoted their lives to conferral of such initiations, the esoteric lineages stemming from this era of Masonic innovation necessarily included the laity. For perhaps the first time in history shoemakers, bakers, journalists, poets, and other craftspeople could be initiated into mysterious societies, secretly assembling behind closed doors to confer weighty titles such as “Supreme Magus”, “Adeptus Major”, “Knight of the Rose Cross”, and “Unknown Superior”. Of course, in an age which immediately followed the Industrial Revolution, as well as several other cultural and political revolutions, and the often oppressive grip of orthodox Christian religious authority, it was of necessity that initiates be drawn from the working class. Rosicrucianism and the movements it inspired can in many ways be seen as a reaction to the destruction of the sacerdotal elite and mystical-theological culture of mainstream religions by the advent of Protestantism and its gradually increasing influence over the educational institutions and intellectual paradigms of the time period.

There were several pro’s to this changing of the guard. This democratization also served to preserve and transmit the esoteric traditions of antiquity while simultaneously evolving them, resuscitating them as living traditions. Another pro was that women were frequently initiated and admitted on equal footing to off-shoot orders such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, as well as the Martinist Order and its related bodies. This opened the practice of ritual magic and the contemplative Mysteries to a broader interpretation and influence. Indeed, there have been tremendous contributions to the culture and practice of the aforementioned by many female initiates such as Moina Mathers (1865–1928), Florence Farr (1860–1917), Maude Gonne (1866–1953), and even Willermoz’s own sister Claudine-Thérèse Willermoz Provensal

(1729–1810). This phenomenon also subtly diffused a sense of the numinous throughout the mainstream by way of art, literature, and music. Péladan, himself a literary figure, held Rosicrucian salons featuring attendees such as the Romantic composers Claude Debussy (1862–1918) and Erik Satie (1866–1925). The Rosicrucian novel Zanoni penned by the English politician Lord Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1851–1866), himself a Rosicrucian initiate, took the public imagination of the 19th century by storm.

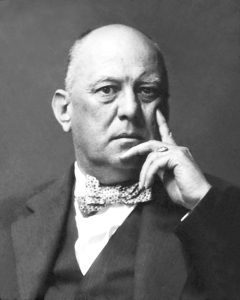

Some con’s on the other hand were a sense of competitiveness, for instance. Notorious 19th century occultist Edward Alexander “Aleister” Crowley () was a member of both the Golden Dawn and the OTO and was maligned and rejected in the main by many of his Adept co-initiates (specifically in the Golden Dawn) and ousted from the OTO by Reuss in the early 1900’s. His response was to establish competing schools, utilizing the structure and inspiration of the organizations of which he was a part while dramatically altering their substance to fit his own interpretations. This claim can of course be made of all the aforementioned orders formed during this period of innovation, but in Crowley we have a good example of what happens when these lineages fall into ill-equipped hands. Specifically in his inversion of the quintessential esoteric formulas and purposes of these Orders.

In describing a more pervasive potential con of the democratization of the Mysteries, I quote from the final paragraph of a chapter entitled “Early Modern Occulture: Spiritualism, Illuminism, Theosophy, & the French Occult Revival” from my forthcoming book A Formless Fire: Rediscovering the Magical Traditions of the West, published by Tria Prima Press:

Admittedly, there has been an appreciable change in tone through the last several chapters taking on a web of chronological relationships and passings of the baton, approaching the nature of a classic grail quest; spanning bygone landscapes, romantic time periods, quixotic personalities, and cryptic orders. Yet we also see the increasing revelation of the mysteries outside of a highly trained priest-class. The initiates of the early-modern era were artists, shoemakers, journalists—workaday people, psychologically and societally more akin to modern men and women than the ancients. Perhaps their Rosicrucian aspirations were a call to adventure in an increasingly industrializing age. In any event, we may wonder if this increasing accessibility and glamorization of the mysteries wasn’t the beginning of the coming hyper-evolution of this trend we see in the current age of information. The reconstructed rites of the mysteries at this time whispered of to select ears in the stands of Freemasonic lodges and quietly practiced after-hours in backrooms and wardrobe closets may have inadvertently opened its doors to an antithetical spirit of joinerism and the thrill of membership in a secret society, within a secret society. Musings aside, this period undoubtedly served to introduce quasi-secular interpretations and cosplay along with a greater mainstream exposure to the sacred traditions of the west, while at the same time further obfuscating its telos from those initiated in form but not in deed. We can likely bet on time to tell us if it has been worth the price of transmission.