Shabbat, Shekhinah and the Solomonic Pillars

Written by Jeremy Chevrier

Who can find a virtuous woman? For her price is far above rubies.

– Proverbs 31:10There was spoilage for the sake of fixing and destruction for the sake of rebuilding.

– Isaac Luria

Union with the divine has been the underlying theme of spiritual traditions since the beginning of man’s long history. Even our modern word “religion” has its etymological origins in the Latin verb religare which means, “to bind”. In Hinduism and Buddhism, the Sanskrit word “yoga” is used to describe various paths or methods of spiritual enlightenment. The word yoga is derived from the Sanskrit root yuj which means to attach, join, harness or yoke – thus also alluding to this concept of a holy union. This paper will attempt to unpack this concept of holy union or marriage and how it symbolically relates to the two pillars on the porch of King Solomon’s temple, the Hebrew Sabbath (i.e. Shabbat) and the divine presence (i.e. Shekinah).

If throughout our history students of Masonry have surrounded them with a host of swarming theories more intricate than the network, and more multitudinous than the pomegranates it is because so many hints of ancient wisdom and secrets of symbolism have of old been hidden within these mighty columns. And if our own studies of the matter lead us to meanings numerous and almost conflicting, we need not worry about it, for a symbol that says but one thing is hardly a symbol at all.1

The Two Pillars – Jachin and Boaz

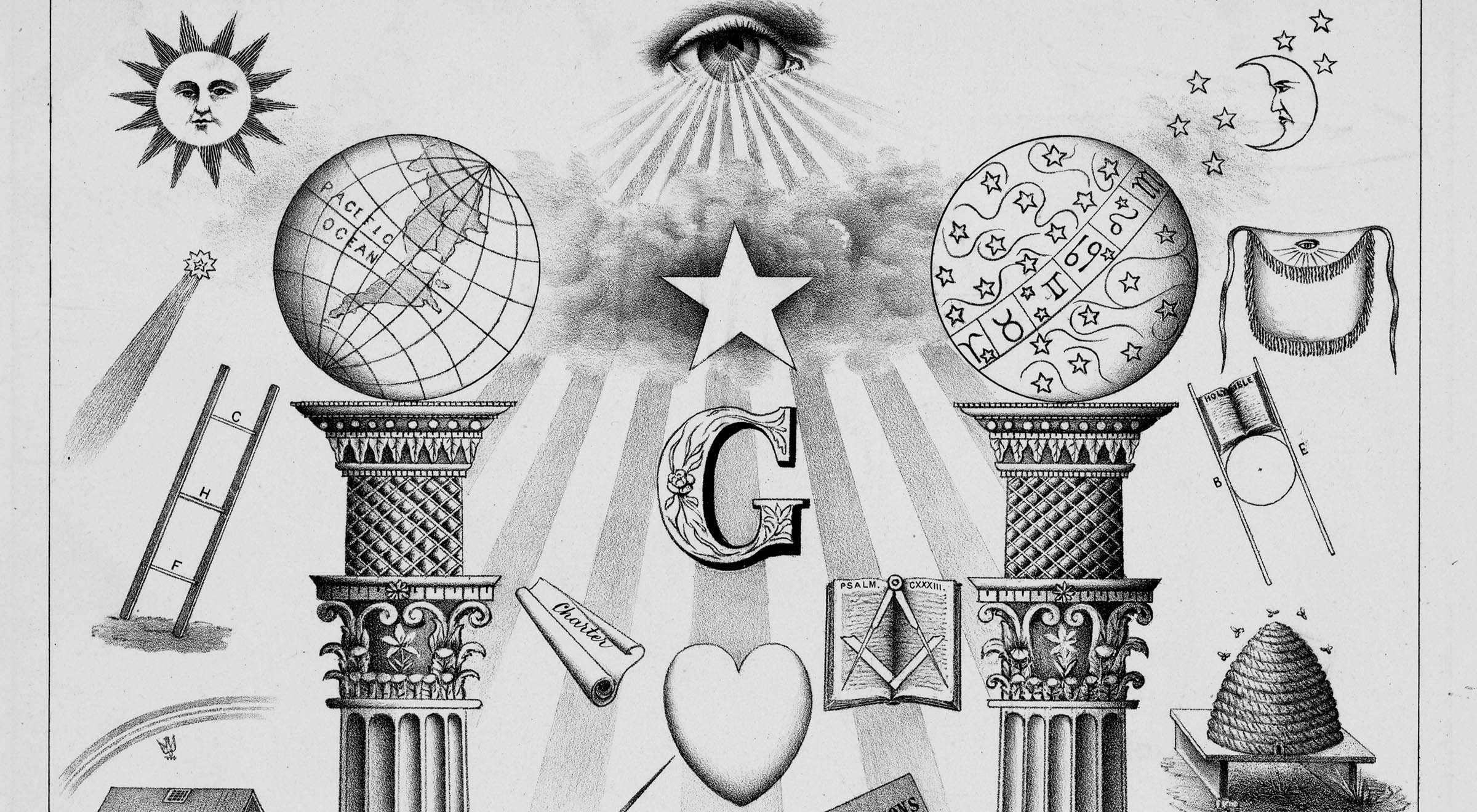

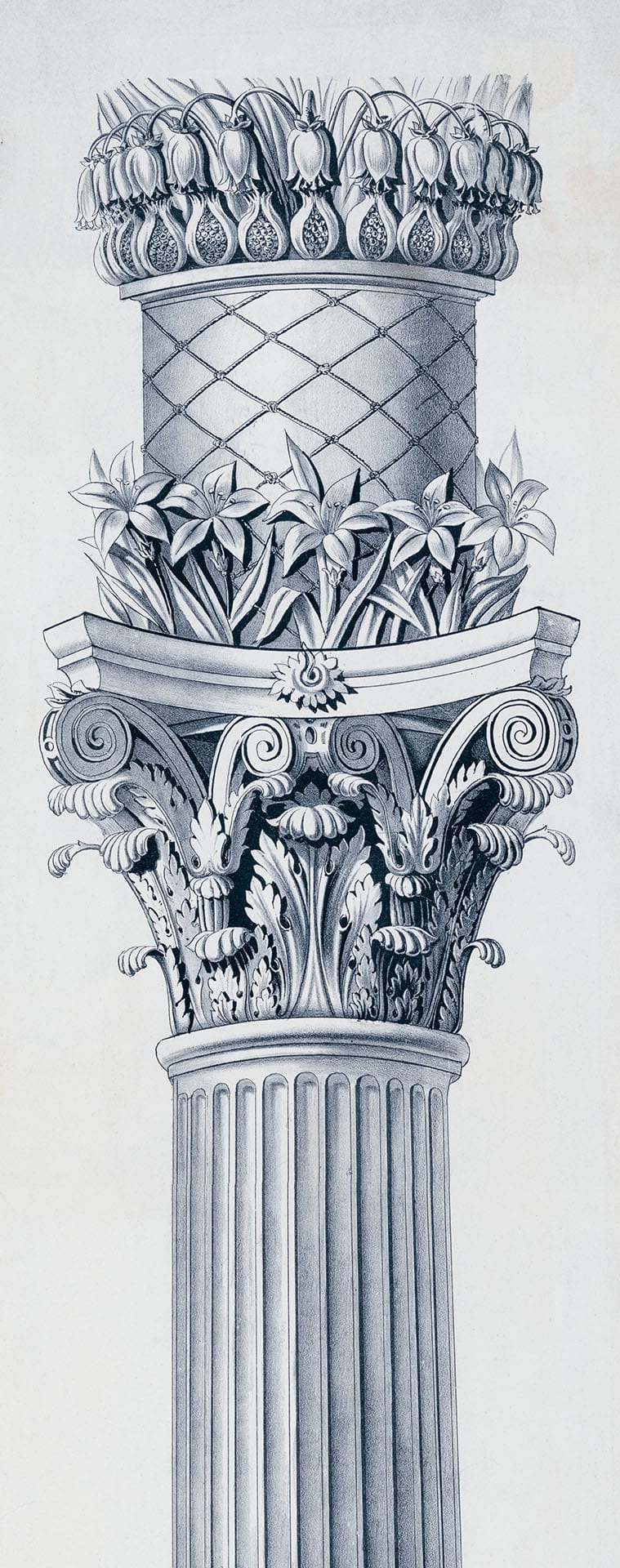

Masons who have been passed to the degree of Fellow Craft will be acquainted with the two pillars that sat outside of King Solomon’s temple – Jachin (in the South) and Boaz (in the North). A detailed description of the two twin pillars is given in 1 King 7 in the Bible. The pillars are described as being cast in bronze by the master craftsman Hiram (Hiram Abiff in Masonry) from Tyre and designed with roundish capitals adorned with networking, pomegranates and lily work. During the Fellow Craft degree, we come to understand that the pomegranates symbolize plenty, the networking – unity, and the lily work – peace. Interestingly, fruit (pomegranates), flowers (lilies) and an interconnected networked system (networking) are common elements within any healthy tree. In Hebrew the names of the two pillars can be understood roughly to mean: 1) Jachin – “He/it will establish” and 2) Boaz – “In him/it [is] strength”.2 Although, it should be noted, the definitive meaning and significance of these two words remains somewhat contested.

Twin, free-standing pillars have commonly been placed at the entrance of temples – going back at least to the ancient Egyptians (e.g. temple of Luxor). The Greeks had the legend of the two pillars of Hercules that are still represented today by the promontories that flank the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar. Interestingly, Plato claimed the mystical island of Atlantis was beyond the pillars of Hercules.3 From ancient times, passing through two pillars was a sign of initiation or of a passing into the mysteries towards a grander purpose.

In ancient Egypt, the gods Horus and Set were regarded as twin living pillars who were builders and supporters of the heavens. Pillars were a way of joining heaven and earth and were often worshipped as gods. Pillars were understood as symbols of stability and the Egyptians described them as “the place of establishing forever”. Although there are many opinions as to what the two pillars standing outside of King Solomon’s temple represented, there is broad agreement that the two pillars reflected some type of duality, or even the concept of dualism and division itself.4

After the Halliwell Manuscript, the Matthew Cooke Manuscript is the second oldest of the Old Charges or Gothic Constitutions of Freemasonry. According to the Cooke Manuscript, before Noah’s flood, Jabal, Jubal and Tubal Cain, “had knowledge that God would take vengeance for sin, either by fire, or water”. Thus, it was critical to write down their knowledge of the seven sciences on the two pillars – one pillar made of a stone that could withstand flooding by floating on water – a stone named “latres” – and one pillar of made of stone that could withstand fire – made of marble. The manuscript then states that Pythagoras found one of the pillars and Hermes found the other, and thus, “they taught forth the sciences that they found therein written.”5 Clearly, masons as well as others throughout history have regarded the concept of twin pillars as a symbolic means of preserving extremely sacred knowledge of some kind for posterity.

Duality and Unity – the Symbolism of the Pillars

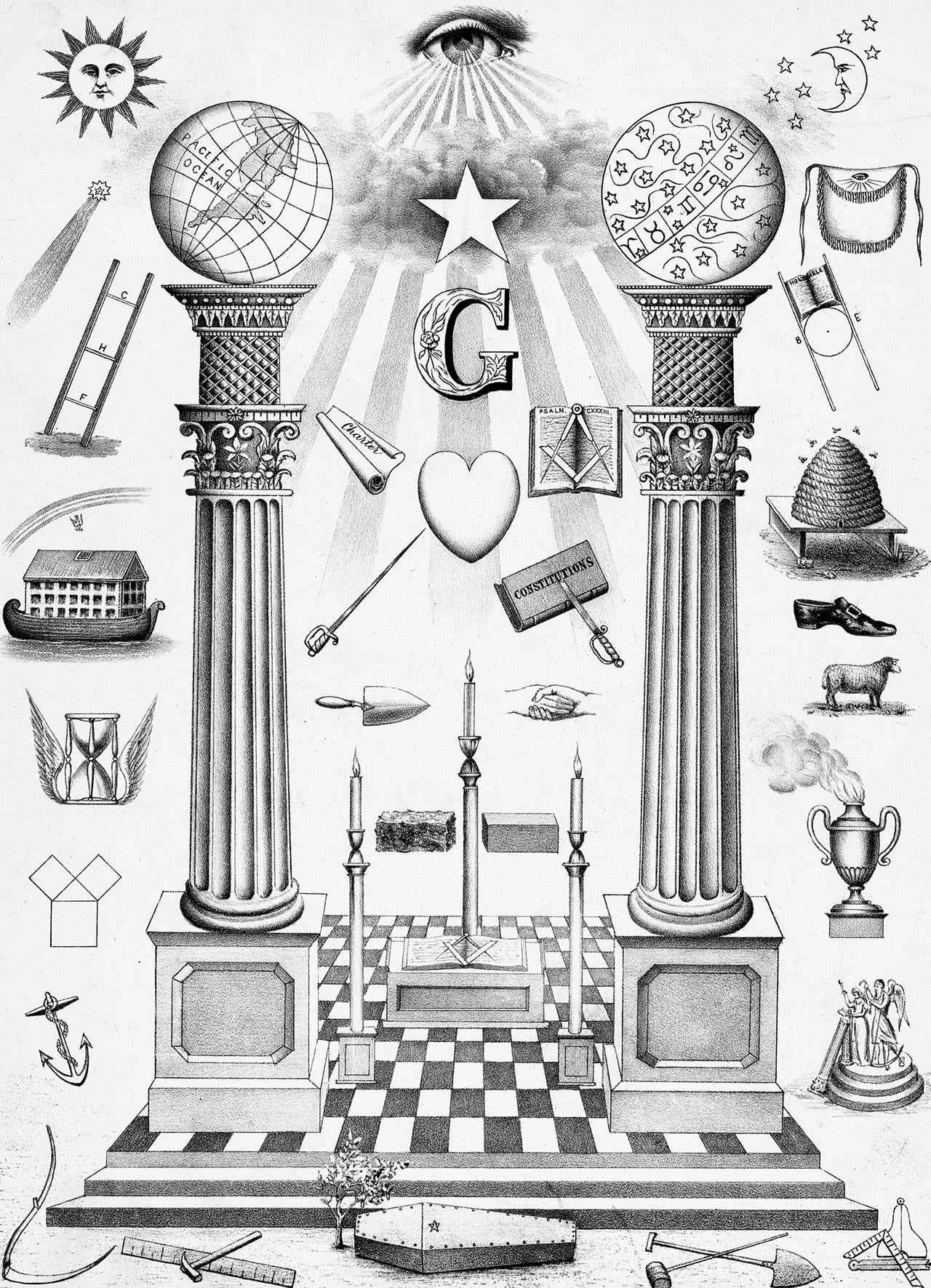

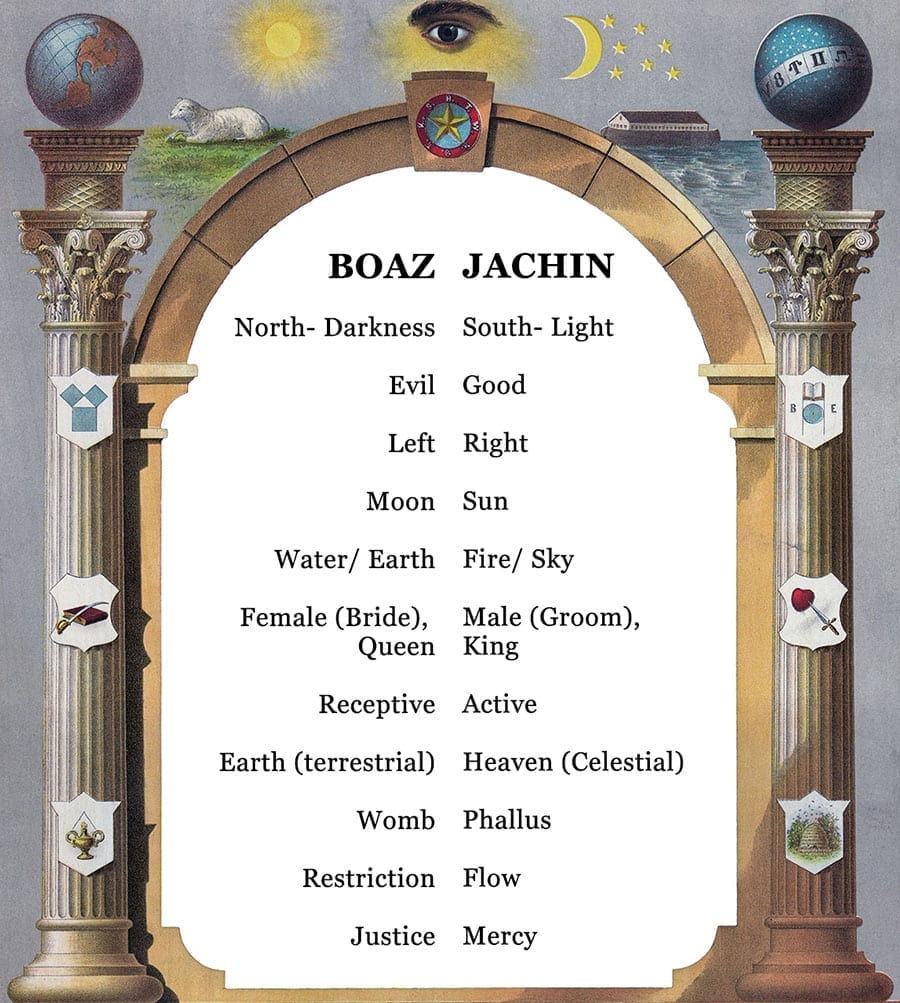

The two pillars of Jachin and Boaz can be seen to represent various polarities. Just in the fact that there are two pillars brings in this dualism concept. Numerologically, the number two represents the first separation from the unity of one, a division and the creation of the world of separate things. In fact, the concept of passing beyond the veil of the world of dualism (in Hinduism know as Maya – illusion) to the state of divine unity, harmony and oneness is a potent way of interpreting the meaning of the pillars for an initiate into the mysteries. Even though this paper argues for one primary interpretation of the dualism represented by the pillars, the reader may appreciate the table below which articulates some other potential polarities the two pillars may represent. These dualities can be seen as “horizontal” or “vertical” in dimension depending on one’s conceptual vantage point. A visualization of Jachin and Boaz in a masonic tracing board is illustrated at the top of this article.

Thomas Troward, in The Two Great Pillars of Boaz and Jachin, provides an argument that the name Jachin can be understood to represent “Yakin” (J and Y are interchangeable in Hebrew) and resolve into the words, “one only,” meaning; all-embracing unity. Troward also argues that Boaz, through the biblical story of Boaz and Ruth, represents, “the principle of redemption in the widest sense of reclaiming an estate by right of relationship, while the innermost moving power in its recovery is Love.”6

In the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, the principle of balance, equilibrium and harmony is revered as possibly the noblest of aspirations. The Royal Arch highlights the symbolic meaning of the key stone that sits at the equilibrium point of the arch that connects (and serves as the point of connection) the two pillars. Blue lodge Freemasonry highlights the importance of harmony, which is the “strength and support” (think Boaz and Jachin) of all institutions, especially the institution of Freemasonry. It is thus clear than some type of unity or union must reside at the heart of the royal art of Freemasonry, and beyond the gates of the great temple. But, what two things in this world are the most important to unite and function in harmony?

The Marriage of Heaven and Earth

Of all the possible dualities that the two pillars could represent, I would assert that man’s desire to connect with his Creator contains the most meaningful and profound symbolism to consider in relation to the two pillars of Freemasonry. It is the “vertical” connection that is most vital to man. Man’s connection to his creator is the holiest of marriages, the union of heaven and earth, above and below, returning creation once again into its primordial perfection and state of completion – the state before the fall. The pillars that must be passed through by the initiate thus reflect the idea that the initiate must recognize this as the goal of his journey – the improvement, perfection and purification of himself to be a vehicle for the supernal divine.

The Kabbalah and the Shabbat Bride (Shekinah)

According to the Jews, the Talmud is considered as the “oral Torah” that unpacks and reveals much of the hidden meaning and details not fully articulated in the Torah (i.e. first five books of the Holy Bible). The Kabbalah is the mystical area of study within the Judaic faith which further unpacks the deepest, most concealed mysteries and veiled symbolism of both the Torah and the Talmud. Much of this understanding is expounded on in the mystical books of the Hebrews, such as the Zohar, the Bahir and the Sephir Yetzirah.

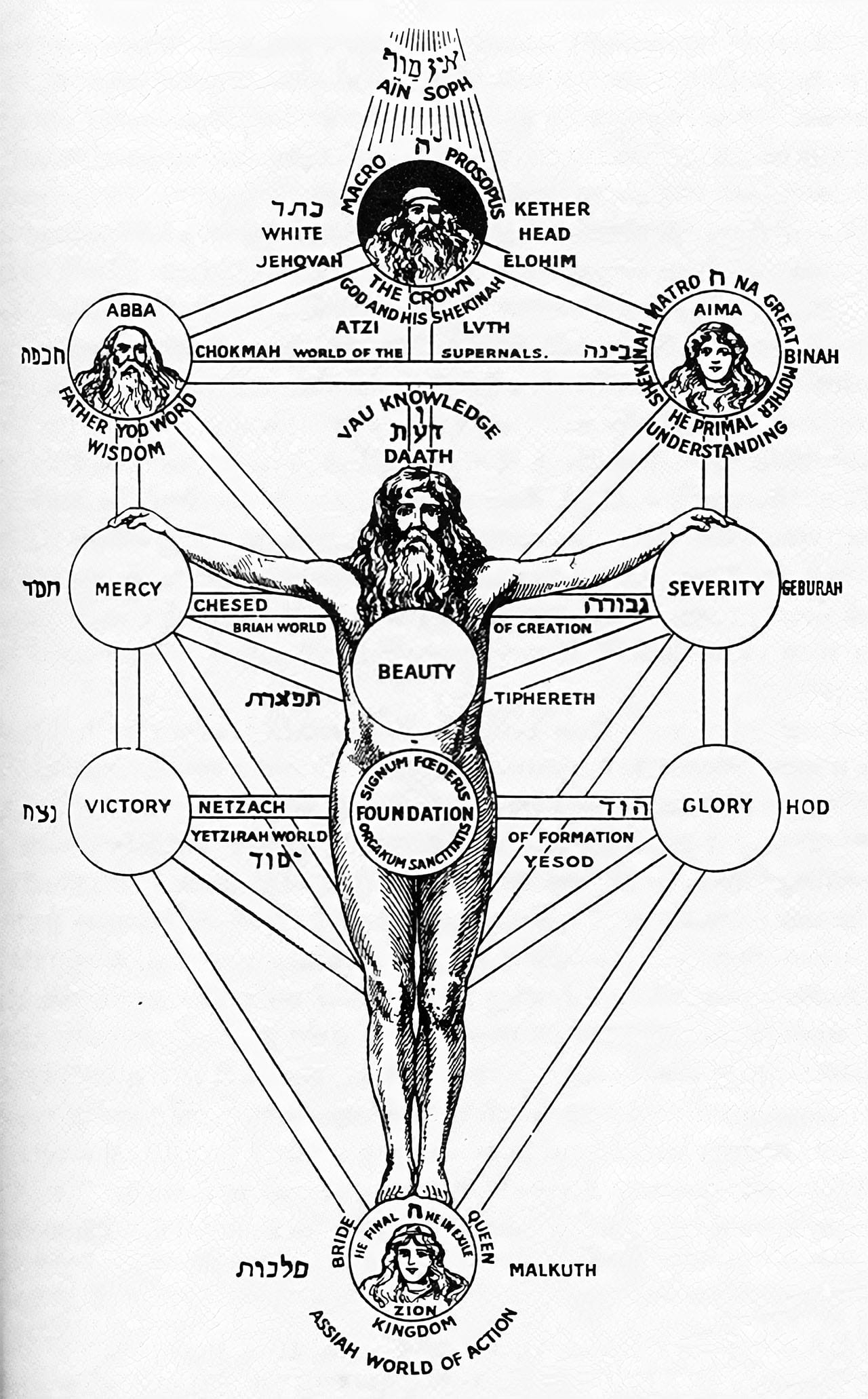

This paper will avoid much of the abstruse complexity that is laden within much of these Kabbalistic resources, and instead attempt to simplify some of the most profound insights from the Kabbalah that can help us as freemasons to understand more deeply the significance of the meaning of the two pillars. As a basic background to the Kabbalah it is important to understand the idea of the 10 attributes or emanations (sephirot) through which the infinite and incomprehensible God (Ein Sof) reveals itself according to Kabbalistic thinking. The accompanying diagram shows all the various sephirot and their 22 various connecting channels which represent each letter of the Hebrew alphabet along with the symbolic correlation of each sephirot to the body of man.

According to the Kabbalah, the bride of heaven (the “divine presence” – Shekhinah) was intentionally concealed within the soul of God’s last creation – man. The Shekhinah was hidden in the world we live in – the bottom/last sephirot of Malkuth – Kingdom. Shekhinah is derived from the word shochen which means, “to dwell within”. The Shekhinah is viewed as female and receptive and can be understood as the “glory” (Hebrew – kavod) of the soul. According to the bible, man was said to be created in the likeness of image of God, the soul of man reflects this likeness in the Shekhinah herself.7 The Shekhinah is also considered to be in a state of “exile” from her husband (the “Blessed Holy One”). Some have likened the Shekhinah to a widow. The 11th-century Talmudic scholar, Judah ben Barzillai al-Bergeloni of Barcelona, described:

When the thought arose in Him [God] of creating His world, He first created the Holy Spirit (ruah ha-qodesh), to be a sign of His divinity, which was seen by the prophets and the angles. And He created the form (demut) of His Throne of Glory, to be the Throne of Glory for the Holy Spirit, called the Glory (kavod) of our God, which is a radiant brilliance (hod boheq) and a great light (‘or gadol) that shines upon all the Creator’s [other] creatures. And that great light is called the Glory of our Creator, blessed be His name and His Glory and His Kingdom forever. And the Holy Scritpure always call the Holy Spirit Glory of our God…And the sages call this great light Shekhinah…And no creature can look at this great light in its beginning (tehillah), no angel nor seraph nor prophet can behold the beginning of this light, because the great power of the light was at its beginning.

According to Genesis, man was created on the sixth day and on the seventh day, God rested. Thus, the seventh day is celebrated by Jews as the holy Sabbath or Shabbat. During Friday evenings, Jews worldwide offer prayers to invite the “shabbat bride”. In fact, symbolically, the “shabbat bride” is the Shekhinah, the female divine presence/glory of the soul within all of us. Shabbat symbolizes the day of the divine union or marriage of man to his creator, when all work and suffering stops and peace again reigns on account of the completion and perfection of the cycle. This marriage is a day of peace (or rest) representing the final “wages” man has earned from his trials and tribulations in this world in his efforts to achieve righteousness, wisdom and understanding. The six days of the work week symbolize mans “works” within this world and the seventh day is when the divine spark, the Shekhinah within man reunites with the heaven above in a holy union which leads to the glory of God and everlasting peace.

In Hebrew, the name for King Solomon is Shlomoh. In the rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s famous commentary on the Bahir he states, “Shalom is spelled with a Vav (from YHVH – tetragrammaton), while Shlomoh is spelled with a Heh (from YHVH – tetragrammaton). As discussed earlier, the Vav represents the Male, while Heh is the Female. Shlomoh-Solomon is therefore the concept of ‘Peace’.”9 Thus, Solomon’s temple can be understood to be the temple of “peace” (i.e. Solomon/Shlomoh/Shalom) that comes about from the holy matrimony of man to his creator – the exiled/widowed Shekhinah to her bride in heaven. In Kabbalah, the groom/heaven is referred to as Zer Anpin (see figure 2). Zer Anpin is the name of the collection/configuration of the six sephirot after the top three (which are considered intellectual or concealed “worlds” and closest to the unfathomable God – Ein Sof). The six sephirot comprising Zer Anpin are: Geburah (severity), Chesed (mercy), Tipheret (beauty), Hod (splendor), Netzach (victory), and Yesod (foundation). These six sephirot are what are referred to as heaven or often the, “The Blessed Holy One”. Critically, according to the Kabbalah, this divine reunion or marriage comes about from righteousness and virtue – the foundation of Freemasonry. Righteousness is our “connection” to heaven. The bottom and last sephirot of the Zer Anpin – known as Yesod (foundation) – plays a connective role similar to the male sexual organ in relationship to uniting the Shekhinah (female generative organ – womb) in Malkuth with the central sephirot of Tipheret (beauty) which lies in the heart of the six sephirot of the Zer Anpin, and the heart of the symbolic Kabbalistic man. The sexual organ and connective power of Yesod is stimulated through righteousness in man, as it is written in Proverbs 10:25 – “The Righteous is the Foundation of the world.” Once Yesod gets aroused the marriage and union of the Shekinah with Tipheret (beauty) above in Zer Anpin takes place, uniting the sephirot into a total of seven (six in Zer Anpin combined with one Malkuth) as a sign of perfection and completion.

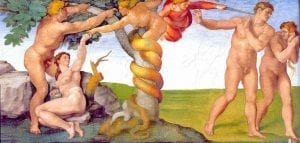

It is critical to note here that this sephirot (Yesod) that plays a “mediating” or connective role between our Shekhinah and heaven (Zer Anpin) above is symbolically placed at the location of the generative organ in the Kabbalistic man (see above). The classic Kabbalistic text of the Zohar states, “When the children of Israel were in exile, the Shekhinah was not perfected below or above. This is because the Shekhinah is in exile with them…the exile is considered the nakedness of supernal Israel.”10 We must also consider that after Adam and Eve tasted of the forbidden fruit in the garden that led to the fall of man, their first reaction was of shame and they covered their generative organs with aprons. Thus, I will assert that the lambskin or white leather apron worn by freemasons during their rituals is in symbolic remembrance of the moment the Shekhinah went into spiritual exile or separation from her husband (heaven above) and became widowed. After all, a widow is a woman who has been separated from her husband, who is not living in this world (Malkuth) and resides in heaven above (Zer Anpin). Thus, all freemasons understand themselves to be sons of the widow.

The temptation of Adam from Michelangelo’s painting from the Sistine Chapel.

This act of moving beyond the pillars symbolizes man’s labor to become virtuous and gain wisdom – which is the key to the connection (sephirot of Yesod) to heaven. According to the Kabbalah, man’s victory over his own evil inclinations on during his journey to righteousness is the ultimate victory and true strength of man, and in this victory is perhaps God’s greatest gift and His purpose behind creation. Rabbi Aryan Kaplan’s commentary on the Bahir explains thus, “The main theme here is the fact the God has maximum pleasure when evil is transformed into good. Man was given free will so as to overcome evil, this being the purpose of creation. When evil is overcome, this purpose is fulfilled, and this is God’s ‘pleasure’.”11

Thinking back to the story of the two pillars from Cooke’s Manuscript, remember that the pillars were made to survive God’s vengeance by water or fire and were meant to preserve the “seven sciences”. Kabbalah explains that the number seven is the number of perfection or completion as God created the world in six days and then rested on the seventh. The seventh, as explained already, was the holiest day and represented the completion and union of heaven and earth – above and below. Seven also reflects the total number of sephirot that will be combined when Zer Anpin (six) marries Malkuth (one) – the Shekhinah bride. In fact, the two triangles interlaced within the star of David symbol, one upwards representing heaven (Zer Anpin) and one pointed downwards (Shekhinah) representing earth, is emblematic of this final embrace of the two lovers, lost, but found again through the efforts of the Craft. When there is a point placed in the center of the star of David – this may symbolize the seventh point in the figure and the completion with the Shekhinah.

This union/connection that we seek after as freemasons is not only reflected in the harmony and peace found in the symbolic marriage of the two pillars or the royal arch, it is also reflected in our most prominent symbol – the square and compass. The square represents the material world and final creation of God with man’s soul (redemption) hidden in it. The compass, which creates spheres, represents all things spiritual and symbolizes heaven (Zer Anpin) above. When the compass overtakes the square, this symbolizes the lost bride of the Shekhinah reuniting and being “crowned” by her lover (the compass) on the sabbath. The groom of Shekhinah is heaven above (Zer Anpin), the compass overtaking the square – the crowning of the unveiled queen. Thus, the individual becomes a “master mason” and, in theory, represents the righteous man who conquers his evil inclination and exemplifies a life of virtue and charity. The book of sacred lore is the holy book (often the bible) that guides every man on his path to self-improvement, knowledge and righteousness. Thus, this holy book, meant to act as the “rule and guide of our faith”, guides the way towards righteous decisions that will allow for the marriage of the square and compass (the two pillars) and the elevation of the Craft more generally. Finally, it is interesting to note that seven or more are needed for the initiation of a candidate into Freemasonry during the entered apprentice degree – thus symbolizing this idea of union from the start of a mason’s journey.

Shekhinah, Sophia and the Prostitute

The Nag Hammadi library is a collection of fifty lost gospels (largely considered heretical by mainstream Christianity) that were discovered in upper Egypt in 1945.12 These books articulate a mystical interpretation of Christianity that existed among the gnostic Christian sects during the time of the earliest known Christians. In many of these books, one can find reference to the female spirit – “Sophia” or wisdom. According to the gnostic understanding, Sophia is akin to the Kabbalistic idea of Shekhinah. Sophia is female and represents the divine spark or light within us all. Sophia represents the human potential for redemption and wisdom within – the fire Prometheus brought from heaven to earth. Sophia is also represented as remorseful and longing to be reunited with her divine lover in the heavenly realms.

What is interesting about some of the gnostic representations of Sophia is that she is often depicted as a prostitute. As counterintuitive as that comparison may seem, the underlying deeper meaning of this reference to the soul as a prostitute is that the soul (Sophia), being divine and pure, is effectively “dragged through mud” of this shameful human world and thus, in a way, is being prostituted through the evil deeds committed by the human bodies that she is concealed within. Thus, the Gnostics represent Sophia as anguished, exiled and eternally longing to return to her androgynous virgin state, united with her groom. Notably, it is possible that Sophia and the Shekhinah may also be alluded to in the Book of Revelations as the whore of Babylon.13 Again, this idea of the shame felt by the Shekhinah in her exile is reflective of the shame felt by Adam and Even after their fall from the garden (heaven), which led to the wearing of the aprons. The apron symbolically covers the shame of the blocked sephirot of Yesod (which is the connective tissue between Malkuth and Tipheret) in the cosmic man. The author John Nash states poignantly about the exiled Shekhinah:

She was the betrothed who had been lost and defiled; now she must be found, re-adorned and reunited with the Holy One, the waiting bridegroom. The notion of defilement was not new; in the Torah God had warned: “Defile not therefore the land which ye shall inhabit, wherein I dwell [shakan]: for I the LORD dwell [shakan] among the children of Israel.”14

According to Kabbalah, justice is allotted from heaven (Zer Anpin) above and received by Malkuth here in our world below. Whenever our choices go against righteousness, the Shekhinah suffers in shame and cries out to her husband above, which generally leads to negative repercussions in our lives which we colloquially identify as the results of “bad karma”. Kabbalah articulates a feedback loop of sorts between heaven (Zer Anpin) and Malkuth (Shekhinah) that allows either mercy or severity (justice) depending on the thoughts, words and deeds we carry forward in our lives. Malkuth is also metaphorically represented as the roots of the Kabbalistic tree, and heaven (Zer Anpin) represents the branches above. Thus, just as the health and nutrients offered through the roots of the tree impact the branches (heaven) above, so too, the branches react and carry their own circulated energies and nutrients to the roots below. It is through this natural law which embodies complex systems theory that teaches man to align to righteousness.

The Cross and the Sabbath

Revelation 22:13 states, “Behold, I am coming soon, and My reward is with Me, to give to each one according to what he has done. 1 am the Alpha and the Omega, the First and the Last, the Beginning and the End.”15 Here, a key concept penetrates under the veil of allegorical narrative. According to the Kabbalah, the first emanation (Keter – crown) of God is associated with the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet – Aleph (which is the Greek Alpha). The last/lowest emanation (sephirot) of God is called Malkuth (kingship) and is the created physical world we all live in. It is also the dwelling place and tabernacle of the widowed bride – the holy Shekhinah – who longs to be reunited with her husband above. This world below – Malkuth – is also associated with the last letter of the Hebrew alphabet – Tav (which is the Greek Omega). Interestingly the older form of the Hebrew letter Tav is also known as the Tau cross – or the original cross.

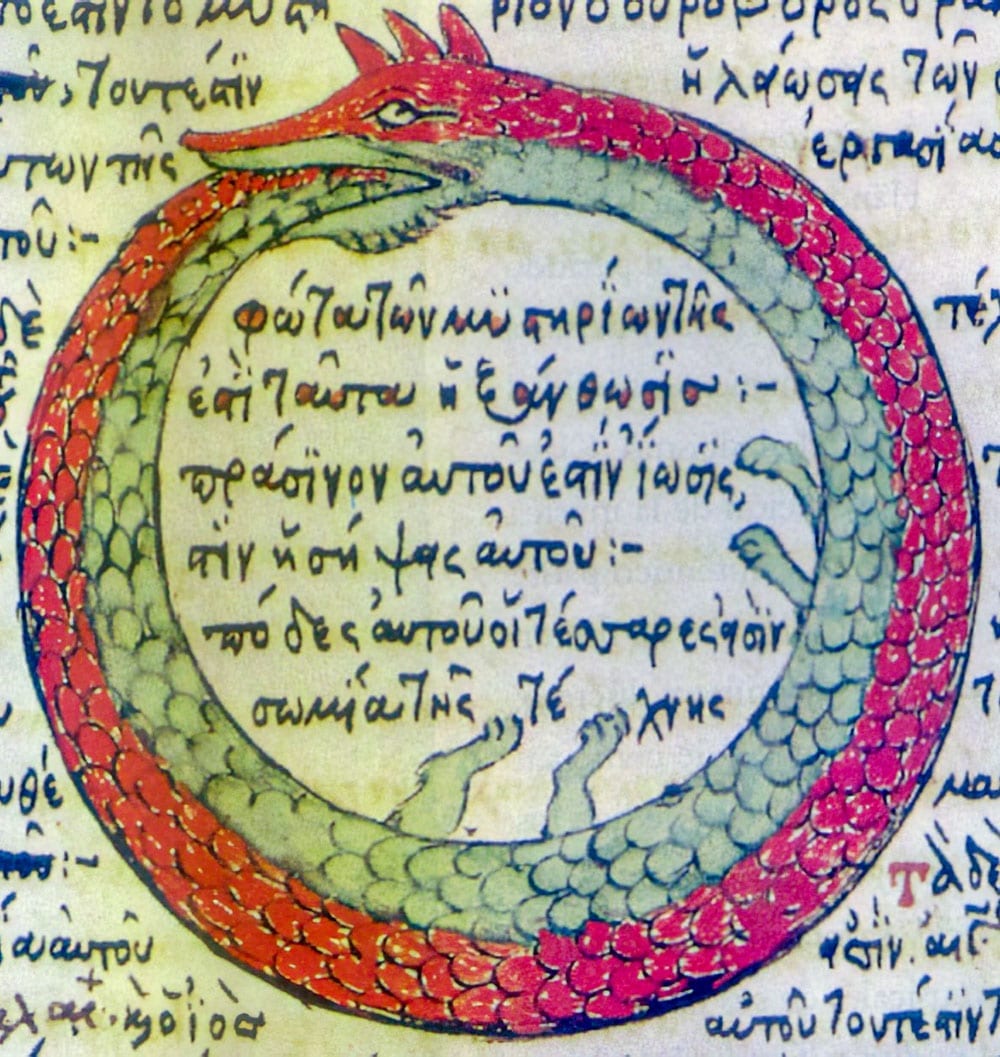

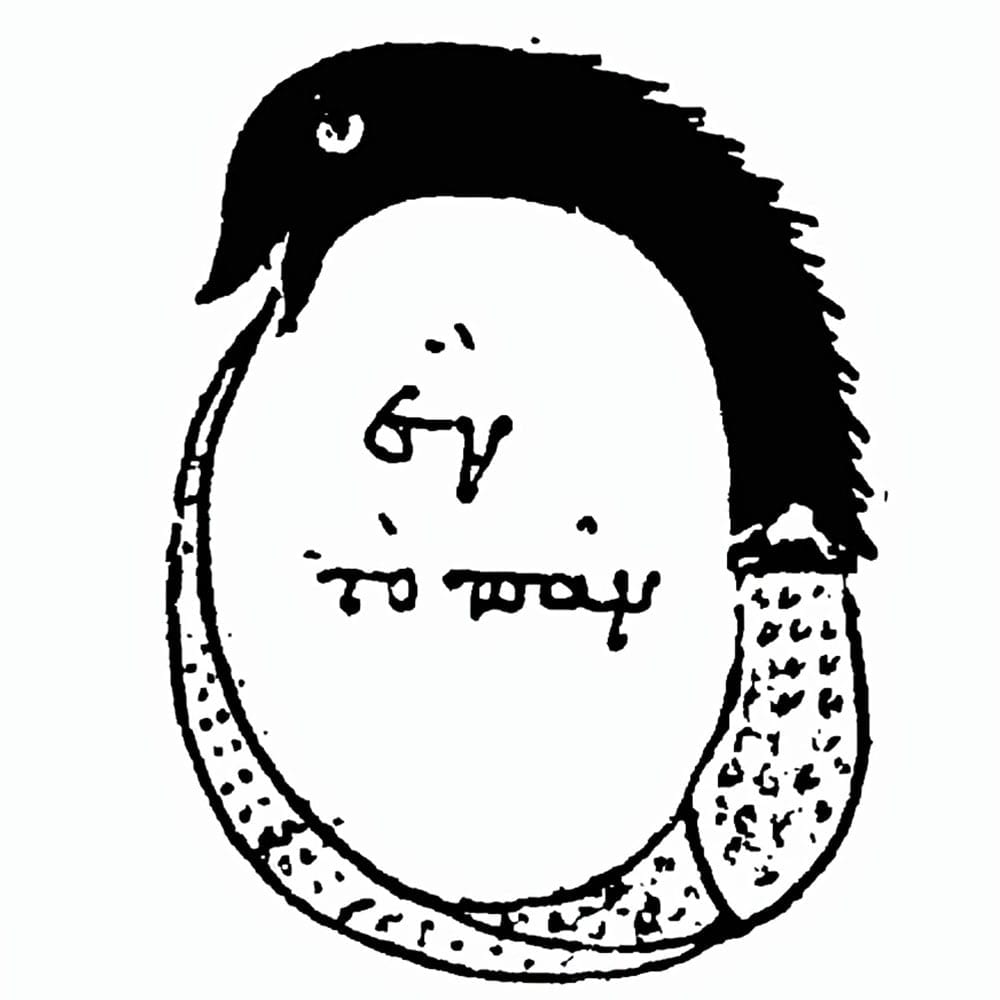

Effectively, when God said he is the Aleph and the Tav, he is saying that he is both concealed and revealed within the furthermost aspect of his emanation or creation – man himself – through the Shekhinah. The Shekinah is the spark within us that is of the same essence as the Creator Himself (he is Aleph and Tav). In our soul, is concealed the sacred bride awaiting – the Shekhinah. The Shekhinah is our connection to our creator and is a part of the creator. This is also part of the significance of the ancient Ouroboros symbol of the serpent eating (Aleph) its own tail (Tav). It is also reflected in the eastern yin-yang symbol where some darkness of yin can be found in the lightness of the yang and vice versa – reflecting again that union and interpenetration of the divine concealed in our world. These ancient symbols also reflect one of God’s purposes in creating the world. According to the Kabbalah, God created his creation so the creation could know him.

According to Rosicrucian sources the Tau cross itself was an ancient symbol of the Craft of Freemasonry.16 This cross symbol can be interpreted to reflect the union process of man connecting to the divine. As freemasons understand signs are made up of right angles, horizontals and perpendiculars – the perpendicular line of the cross represents heaven (Zer Anpin) and the horizontal line represents earth/man/Shekhinah, the right angle is at their intersection. When these two lines cross and unite into one symbol the shabbat bride resides once again in infinite and eternal peace and glory with her groom – heaven above. This is what is meant by “life”.

Critically, the cross should be understood as a sign of the path of righteousness, virtue and moral integrity, as righteousness is the alchemical agent (which arouses the connecting sephirot of Yesod) required to bring about the sacred marriage of these two pillars we have been alluding to. The path in the Kabbalistic Tree of Life diagram travelling from the sephirot of Malkuth to unite with the sephirot of Yesod (in Zen Anpin) is represented by the Hebrew letter Tav. Thus, this ancient symbol of the cross (Tav/Tau) that has played such a central role in the spiritual aspirations of mankind since time immemorial, is the symbol of the path of righteousness (Hebrew – tzedakah) that unites and compels man on his upward/inward journey to the divine. Through marriage, by the crossing of these two great symbolic pillars, we enter the inner sanctum sanctorum of King Solomon’s temple of peace.

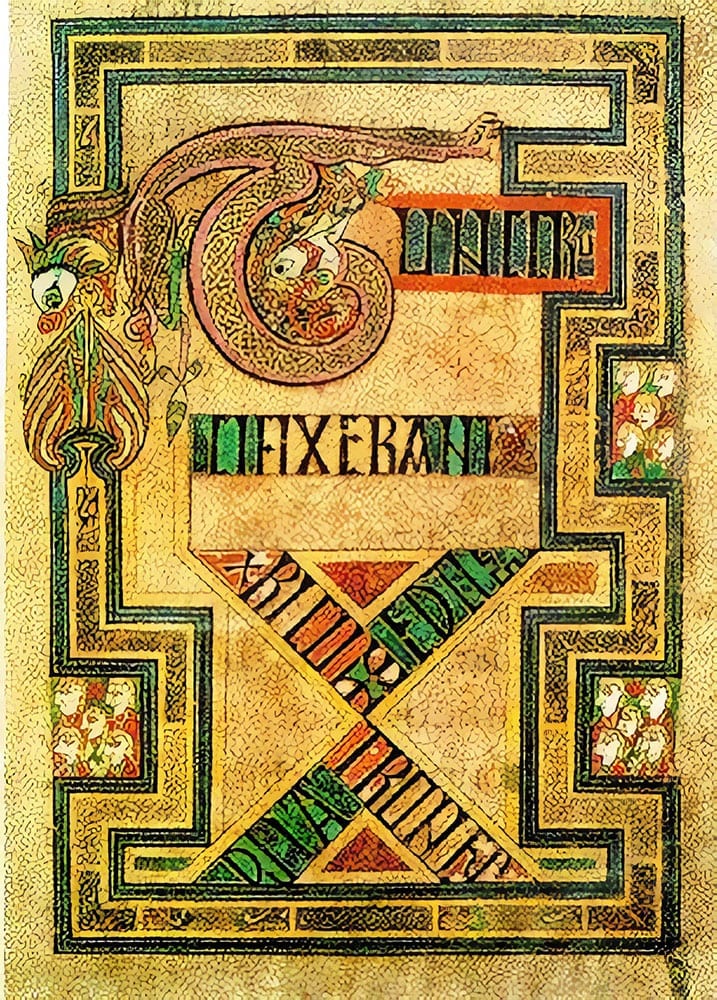

Ouroboros examples

Photo 1– Ouroboros drawing from 1478 by Theodoros Pelecanos of an alchemical tract attributed to Synesius. Photo 2– Engraving of an wyvern-type ouroboros by Lucas Jennis, in the 1625 alchemical tract De Lapide Philosophico. The figure serves as a symbol for mercury. Photo 3– First known representation of the ouroboros on one of the shrines enclosing the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun. Photo by Djehouty/ Wikipedia Photo 4– A highly stylized ouroboros from The Book of Kells, an illuminated Gospel Book (c. 800 AD). Photo 5– Early alchemical ouroboros illustration with the words ἓν τὸ πᾶν (“The All is One”) from the work of Cleopatra the Alchemist in MS Marciana gr. Z. 299. (10th Century).

Bibliography

Bibliography

Adilman, Binyomin. “Sabbath Soul.” Chabad.org.

Ariel, David S. “Mystical Shabbat.” Myjewishlearning.com.

Brown, Raymond J. “The Pillars.” Mastermason.com.

Carr, Harry. “Pillars and globes, columns and candlesticks.” Freemasonry.bcy.ca.

Cassaro, Richard. “The Kundalini Kings: Masonic Symbolism in French Royal Art & Architecture.” RichardCassaro.com.

Conner, Miguel. “Rise of the Whore Goddesses: Sophia and Babalon.” Thegodabovegod.com.

Dawkins, Peter. “Beauty, Truth and the Gemini.” Fbrt.org

Falconer, Don. “The Three Great Pillars.” Themasonictrowel.com.

Fawcette, W. L. “History of the Two Pillars.” PhoenixMasonry.org

Freeman, Tzvi. “Who Is Shechinah, And What Does She Want from My Life? Exile of the Shechinah and descent of the soul.” Chabad.org.

Heindel, Max. Freemasonry and Catholicism. Global Grey, 2013.

Kaplan, Aryeh. The Bahir – Illumination. York Beach, Maine. Samuel Weiser, Inc., 1979,

Lewis, Rhona. “The Meaning Behind the Flames.” Chabad.org.

Luria, Rabbi Yitzchak. “Old & New Souls: A Review.” Chabad.org.

Mackey, Albert. The Two Great Pillars of Boaz and Jachin. Lamp of Trismegistus, 2020

Matt, Daniel C. The Zohar – The Complete Set. Stanford. Stanford University Press, 2018.

Meyer, Marvin. The Nag Hammadi Scriptures: The Revised and Updated Translation of Sacred Gnostic Texts Complete in One Volume. Harper One, 2009.

Miller, Moshe. “Chesed, Gevura, & Tiferet.” Chabad.org.

Nash, Josh. “The Shekinah: the indwelling Glory of God.” The Esoteric Quarterly (2005).

Palazzo, Robert. “The Esoteric Meaning of the Twin Pillars Boaz & Jachin.” Rimasons.org.

Plato. Timaeus and Critias. Penguin Classics, 2008.

Sharman, Walter. “…Beside the pillar…as the manner was. (2 Kings 11, 14).” Freemasonry.bcy.ca.

Shurpin, Yehuda. “Four Reasons Shabbat is Compared to Bride and a Queen.” Chabad.org.

Speth, George. The Matthew Cooke Manuscript. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013.

Tilghman, Joshua. “The Pillars of Jachin and Boaz, Kundalini, and the Shekinah.” Spiritofthescripture.com.

Tov, Baal Shem. “Passionate Union of Opposites.” Chabad.org.

Weisberg, Chana. “Malchut and the Feminine – Part 1 and 2.” Chabad.org.

Wikipedia, 2020. “Tohu and Tikun.” Last modified December 29, 2019.

Wisnefsky, Moshe Yaakov. “Honoring the Masculine and Feminine (from the teachings of Rabbi Yitzchak Luria).” Chabad.org.

Footnotes

Notes

- Mackey, Albert. The Two Great Pillars of Boaz and Jachin. Lamp of Trismegistus, 2020.

- Mackey, Albert. The Two Great Pillars.

- Timaeus and Critias. Penguin Classics, 2008.

- Mackey, Albert. The Two Great Pillars.

- Speth, George. The Matthew Cooke Manuscript. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013.

- Mackey, Albert. The Two Great Pillars.

- Kaplan, Aryeh. The Bahir – Illumination. York Beach, Maine. Samuel Weiser, Inc., 1979,

- Nash, Josh. “The Shekinah: the indwelling Glory of God.” The Esoteric Quarterly (2005).

- Kaplan, Aryeh. The Bahir.

- Matt, Daniel C. The Zohar – The Complete Set. Stanford University Press, 2018.

- Kaplan, Aryeh. The Bahir.

- Meyer, Marvin. The Nag Hammadi Scriptures: The Revised and Updated Translation of Sacred Gnostic Texts Complete in One Volume. Harper One, 2009.

- 17

- Nash, Josh. “The Shekinah: the indwelling Glory of God.” The Esoteric Quarterly (2005).

- 22:13

- Heindel, Max. Freemasonry and Catholicism. Global Grey, 2013.

Written by Jeremy Chevrier

Want to hear when new articles and podcasts are published??

Subscribe to our Newsletter.