Trismosin’s Truffles: Mushrooms Revealed in Alchemy’s Most Famous Manuscript

Written by P.D. Newman

In 1995, taking investigative cues from Wasson, Hofmann, and Ruck’s 1978 work, The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries, Clark Heinrich published a remarkable book titled Strange Fruit: Alchemy, Religion and Magical Foods, updated in 2002 as Magic Mushrooms in Religion and Alchemy.

As the titles reflect, Heinrich’s primary concern was to explore the possible use of magic mushrooms in Alchemical works. The evidence he amassed is both exhaustive and convincing. However, there is one glaring instance of mushrooms occurring in Alchemy which somehow failed to receive treatment in Heinrich’s study.

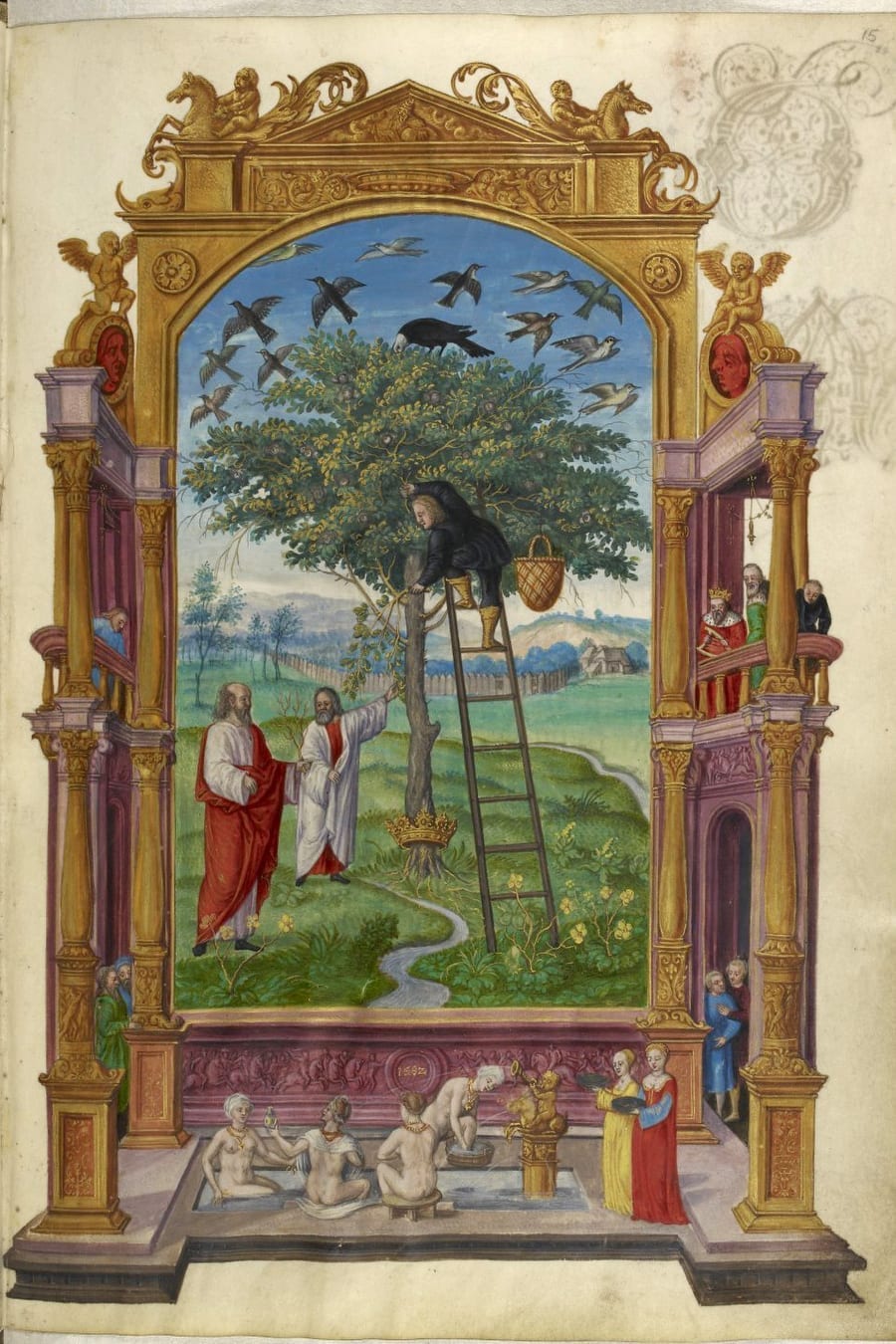

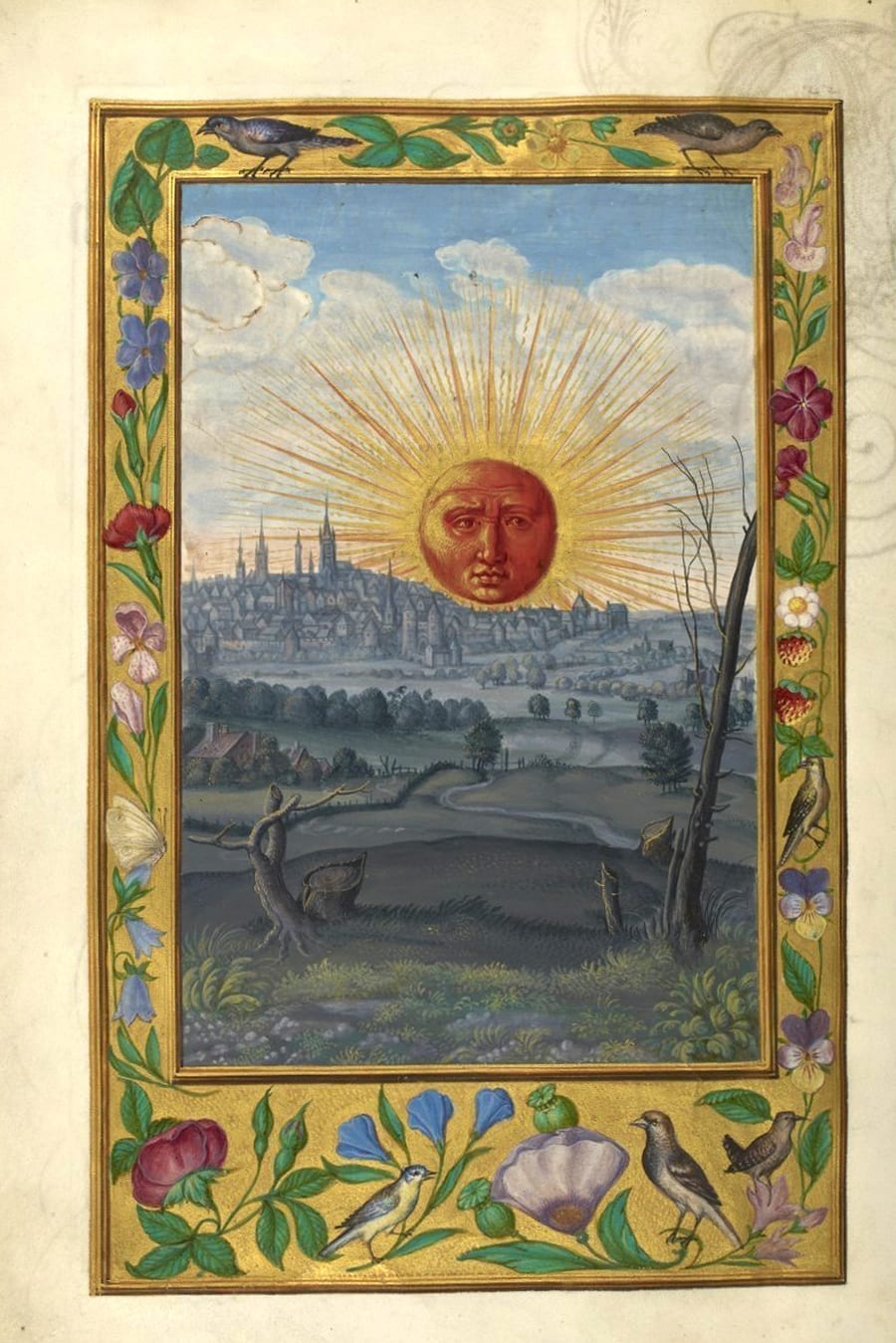

Perhaps the most obvious depiction of mushrooms in an Alchemical manuscript appears in Salomon Trismosin’s 16th century text, Splendor solis, touted by Australian occultist and author, Stephen Skinner, as “the world’s most famous Alchemical manuscript.”(1)

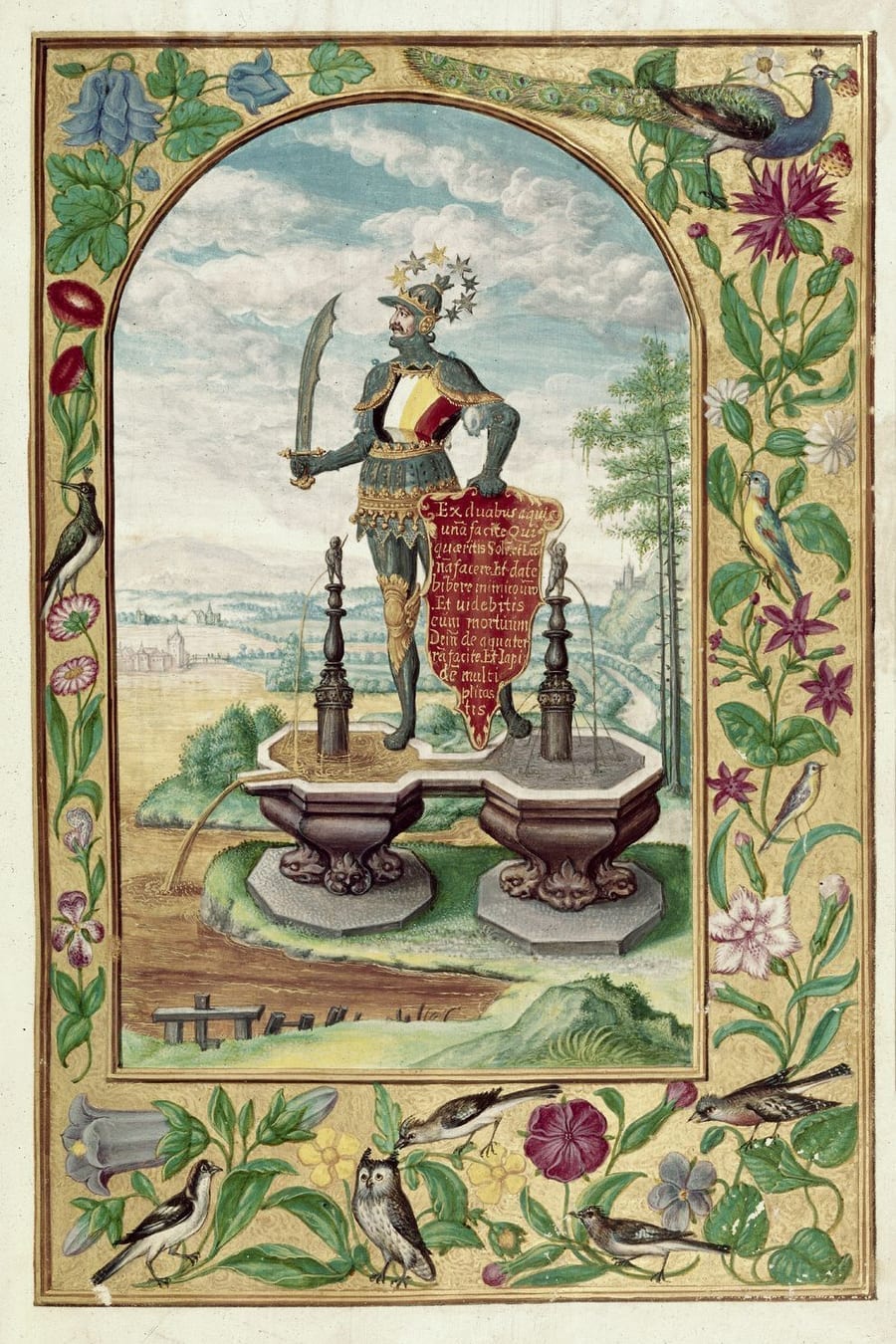

Along the top of the border of plate 5, appropriately titled Mining the Ore, can be seen two plump infant-style cherubs handing over what is clearly defined as golden mushrooms to two dark-colored birds – a probable hint as to the nature of the specimens. For, as amateur mycologist, R. Gordon Wasson, the father of ethnomycology, observed in a 1979 article for Afghanistan Journal, “raven’s bread” is a common epithet for some magic mushrooms.(2)

One reason for this curious association of the ravens with mushrooms is perhaps the visual likeness of, say, Amanita mascara var. gessowii, to an egg that has fallen from a tree and cracked open. Amateur mycophile Erlon Bailey suggests (2b):

“This benefits the fungus by attracting carrion eaters that act as vectors for spore dispersal. The colors yellow, red and white {mimic} the fat, muscle and bone of an animal.”

Additionally, directly below this curious scene of babes and birds is a golden, rainbow-like arch lined with even more mushrooms – more than thirty of them, to be precise. This is something the artist made sure the viewer would perceive.

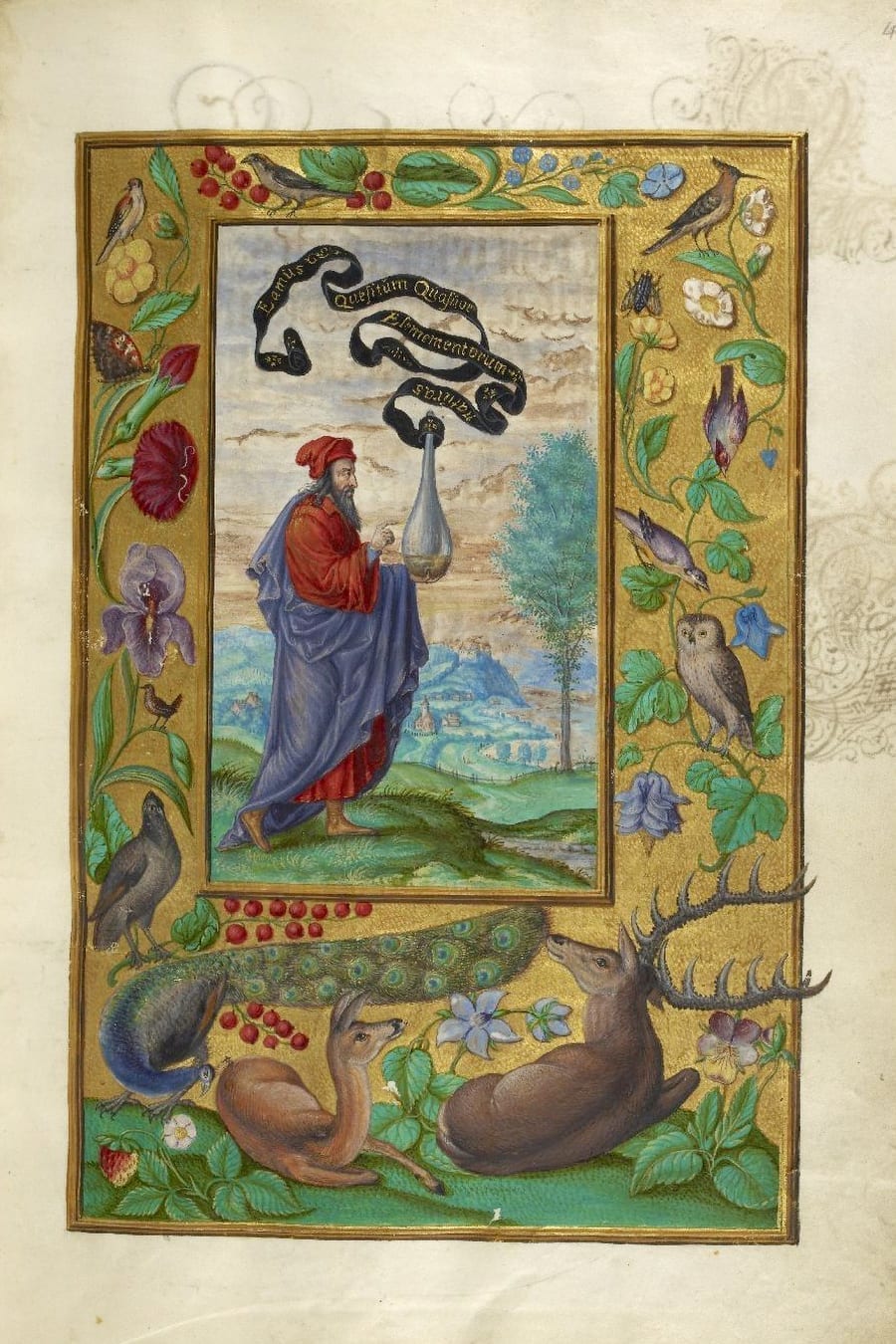

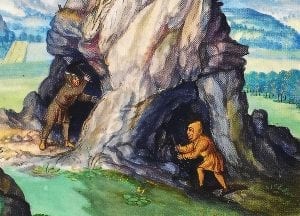

According to Polish historian of Alchemy, Dr. Rafal T. Prinke, plate 5 of Splendor solis has its source in an earlier image found in another popular Alchemical treatise from the previous century, Aurora consurgens, spuriously attributed to Thomas Aquinas.(3) This is plain enough. Central to both images are two cloaked and hooded gnome-like miners, pickaxes in hand, hollowing out a cavern inside of a mountain of jagged rock. Although, Aurora consurgens lacks the decorative golden frame of Mining the Ore in Splendor solis, as well as the biblical scene depicted at the base and other particulars. We’ll address these and other artistic anomalies below.

Mining the Ore too lacks something which Aurora consurgens displays; namely, a pelican plucking at its own breast in order to nurse several accompanying chicks with her own blood. Without spending too much time on an image which is conspicuously lacking from Splendor solis, we do think it worth mentioning that Heinrich was wont to view the pelican as a type of the phoenix, to which he applied a memorable, naturalistic interpretation.

“There are many bird analogues for the arcane substance…but none so perfectly matched to the life-cycle of the mushroom as the phoenix. It is the red firebird, hatched from an egg, which spends all of its life in its nest. It feeds its young with drops of blood, meaning that young mushrooms will be round and the colour of blood. It lifts its fiery wings and ‘consumes itself’ in flames, leaving nothing but ‘ashes’ in the nest.

…Some versions of the myth say the bird becomes a worm after it burns, an allusion to the worm infestation that is likely to occur by the time the mushroom’s ‘wings’ are fully uplifted; when they finish their work in an unharvested specimen only worms and ‘ash’ remain in the nest. From its own ashes the firebird will then be reborn, whether phoenix or fly agaric.”[4]

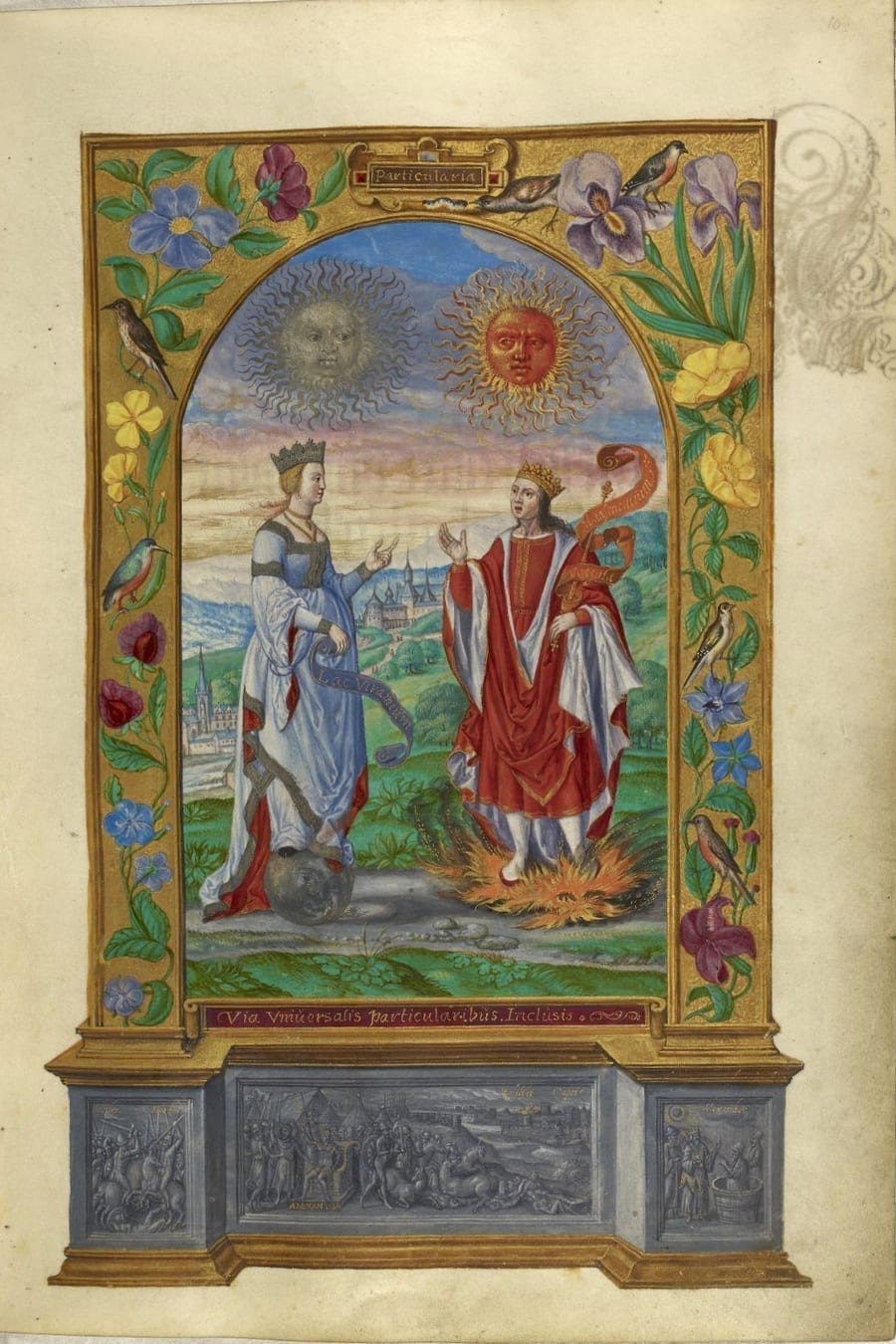

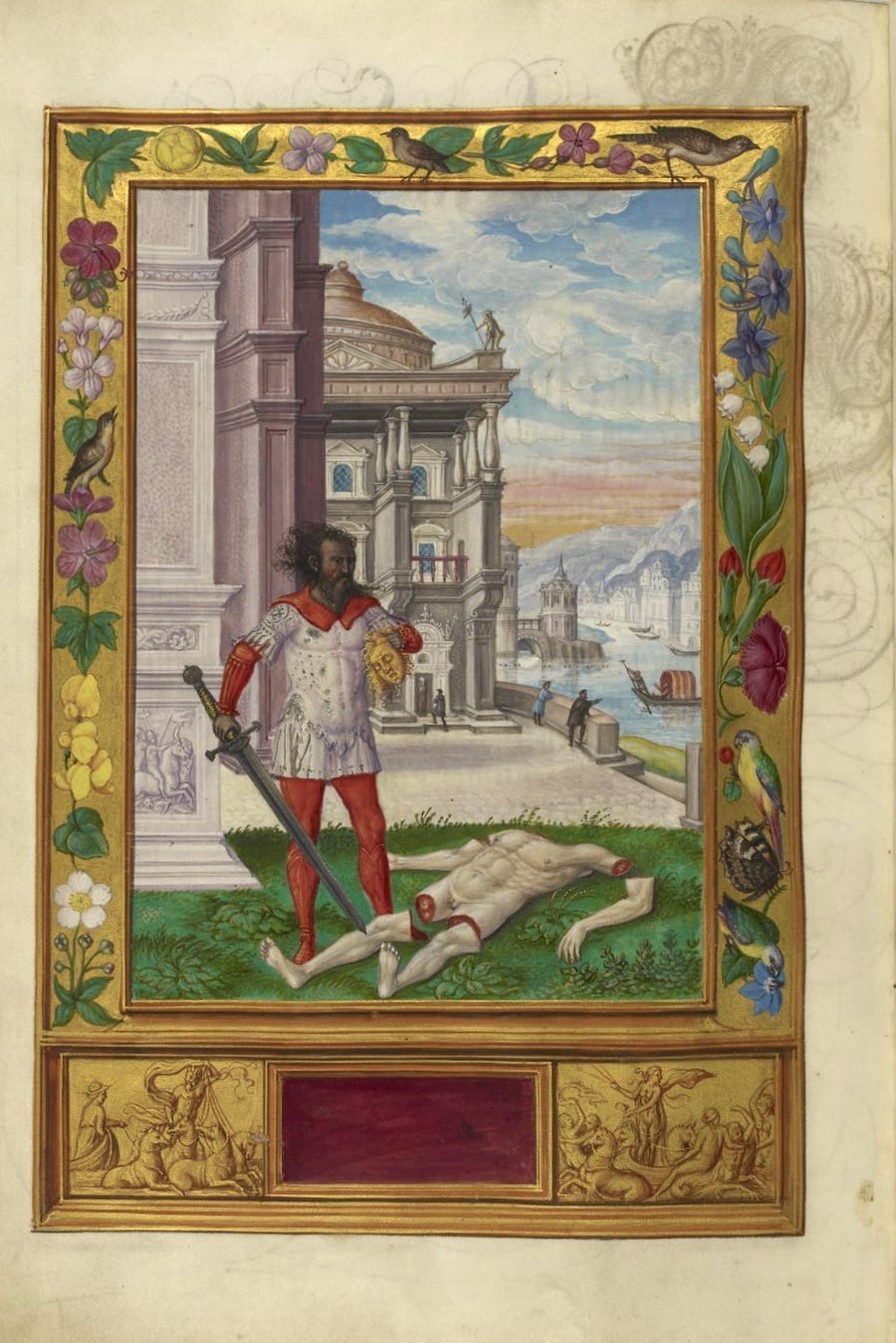

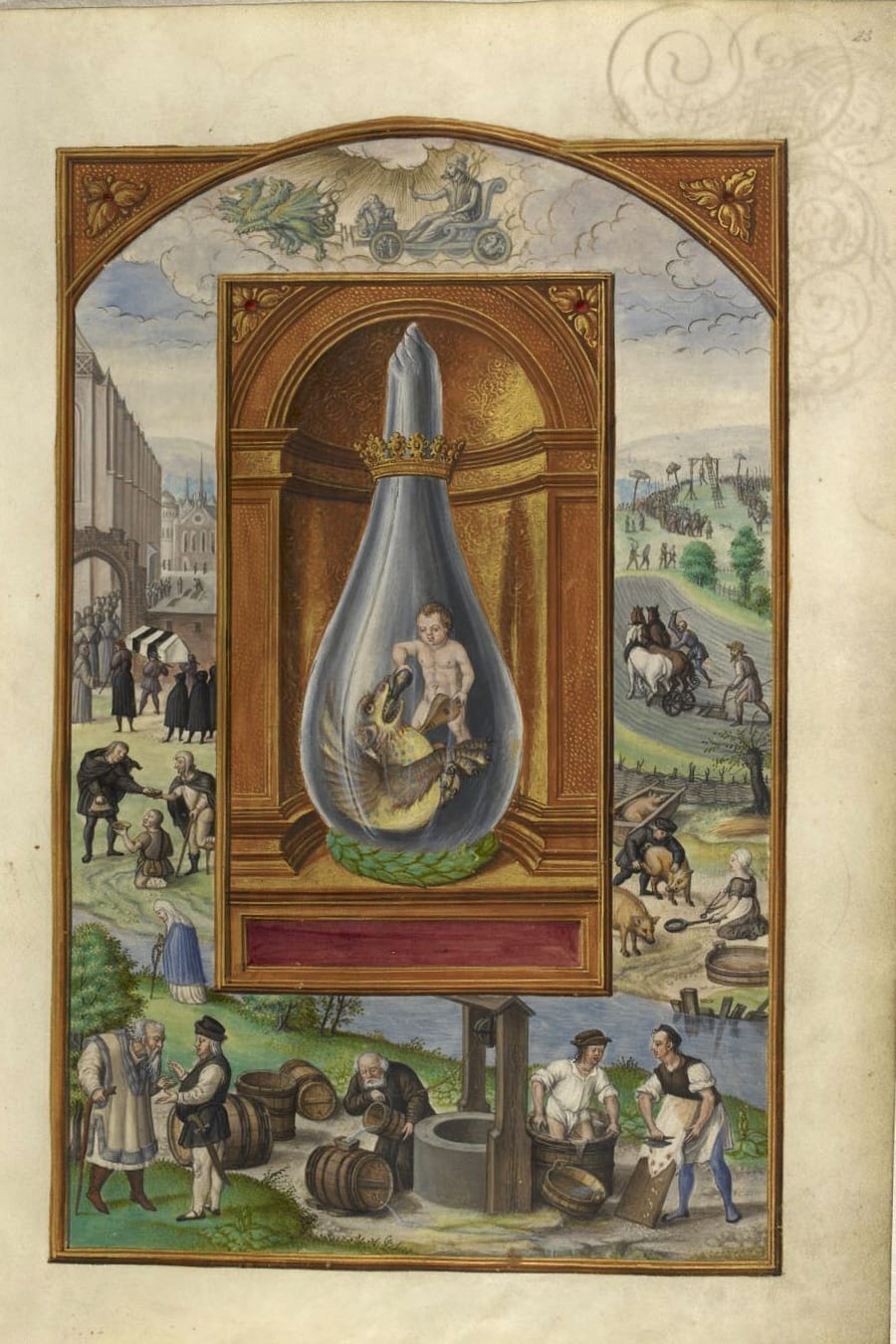

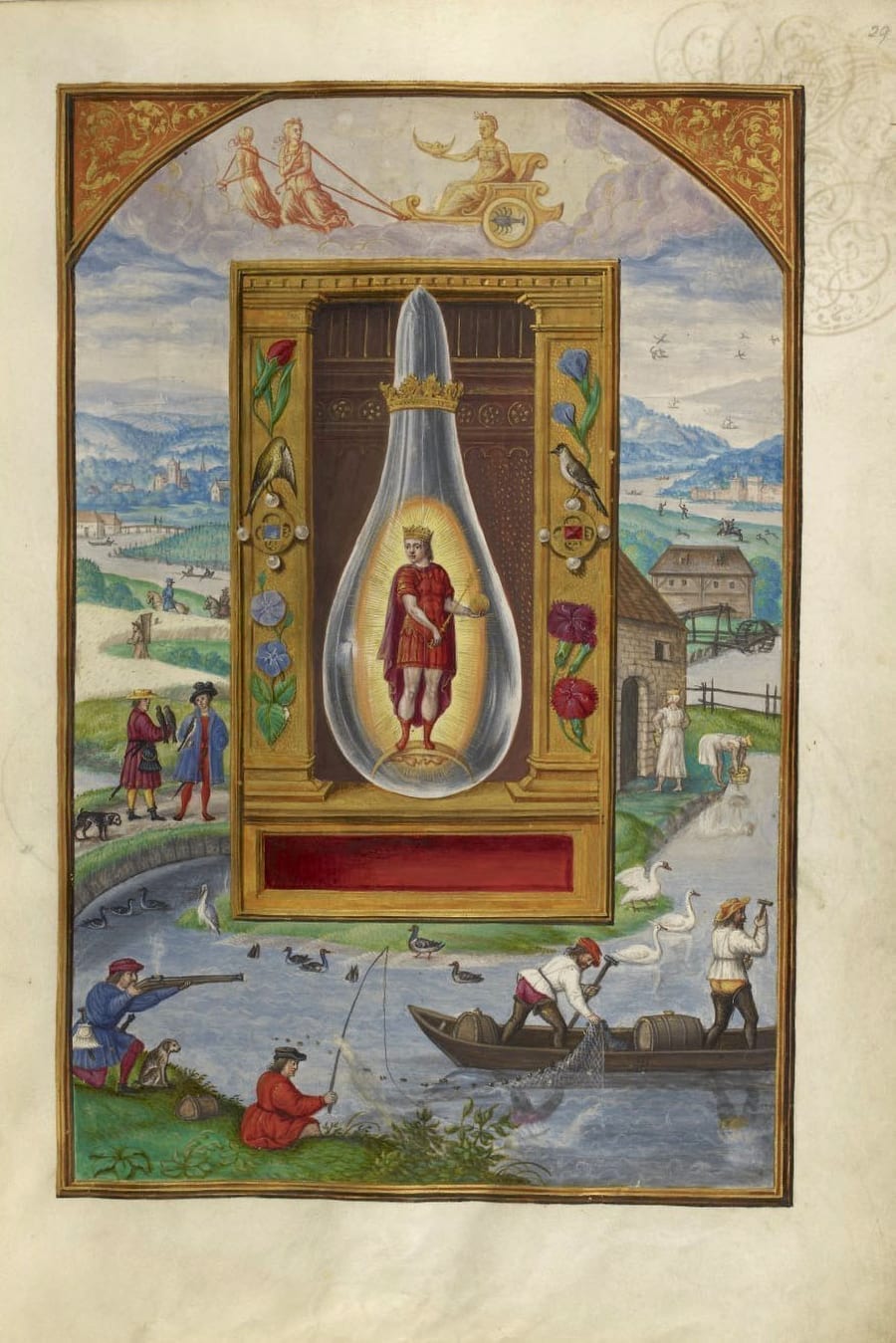

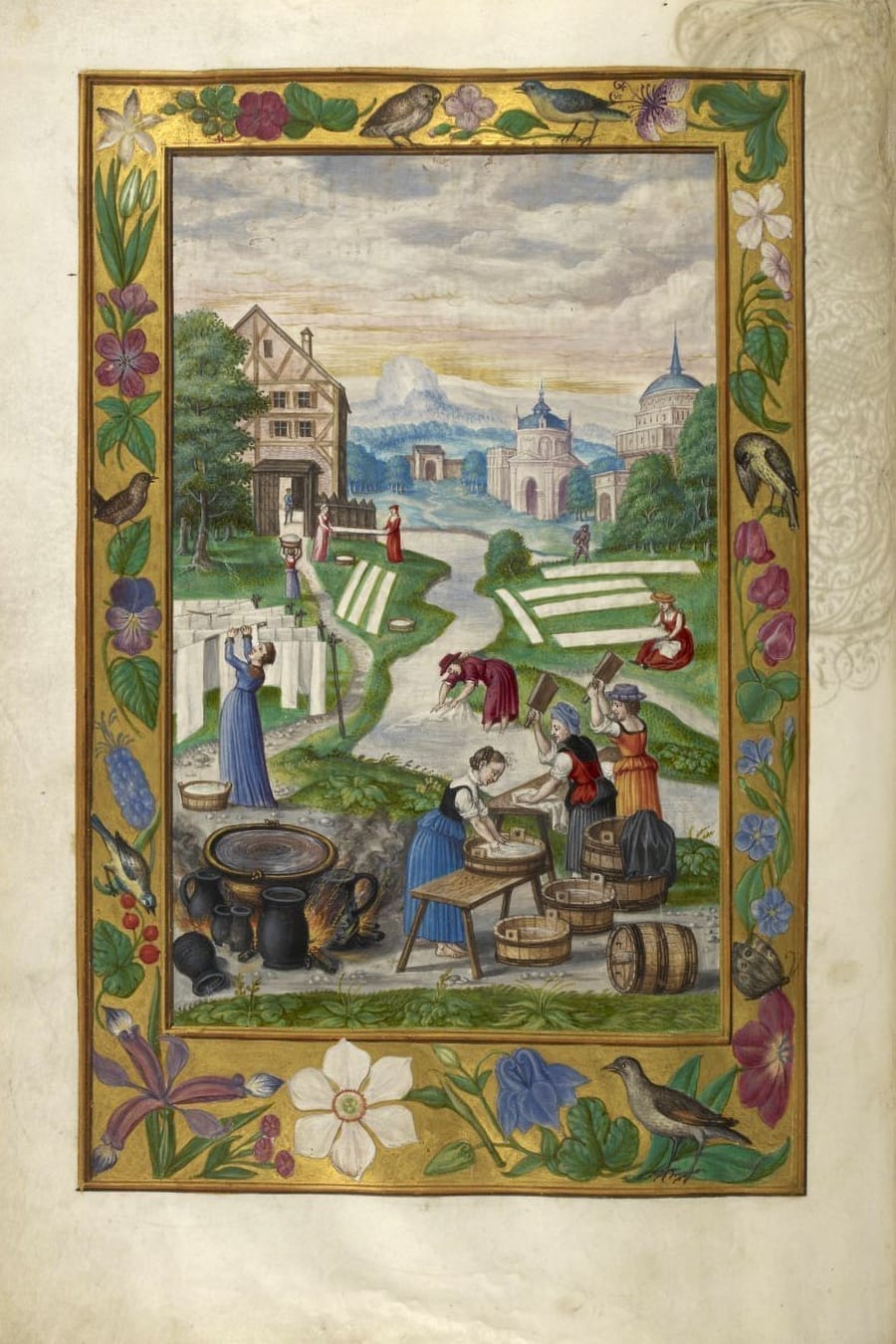

Illustrated plates of the Splendor Solis

A slideshow of all the illustrated plates in the Splendor Solis from 1582. The manuscript is found in the collections of the British Library.

We’ll encounter more naturalistic explanations like this one below. However, we must first answer the question of what metallic ore has to do with magic mushrooms? Aside from the obvious fact that they both seem to spontaneously proceed from the earth apparently unsown and without progenitor, Heinrich observes that well-preserved, dried specimens take on the unmistakable appearance of fired gold. In fact, there is evidence that some species of psychedelic mushrooms are actually rendered more potent through firing. In the case of Heinrich’s treasured Amanita muscaria, for example, flaming converts the toxic and undesirable ibotenic acid into the psychedelic compound, muscimol, thereby making metallurgy a fitting – albeit curious – metaphor. More obvious, though, is the fact that the mountainous structure in plate 5 of Splendor solis has decidedly taken on the subtle appearance of a fruiting body. Furthermore, one is tempted to associate the colors of the two miners’ outfits, ruddy gold and tawny brown in Mining the Ore, and fire red and blue-gray in Aurora consurgens, with two of the most famous magic mushrooms: the mycorrhizal Amanita muscaria and the coprophilous Psilocybe cubensis.

It is clear that, in borrowing from Aurora consurgens, the artist behind plate 5 in Splendor solis, by adding the delicate golden boarder in Mining the Ore, with all of its mushrooms, babes, and blackbirds – as well as the obtuse inclusion of the biblical scene at its base, felt that he was somehow expanding upon or illustrating the message already conveyed in the image of the miners and pelican. Let us see if his innovative additions actually shed any light on the possible meaning(s) contained in the original painting.

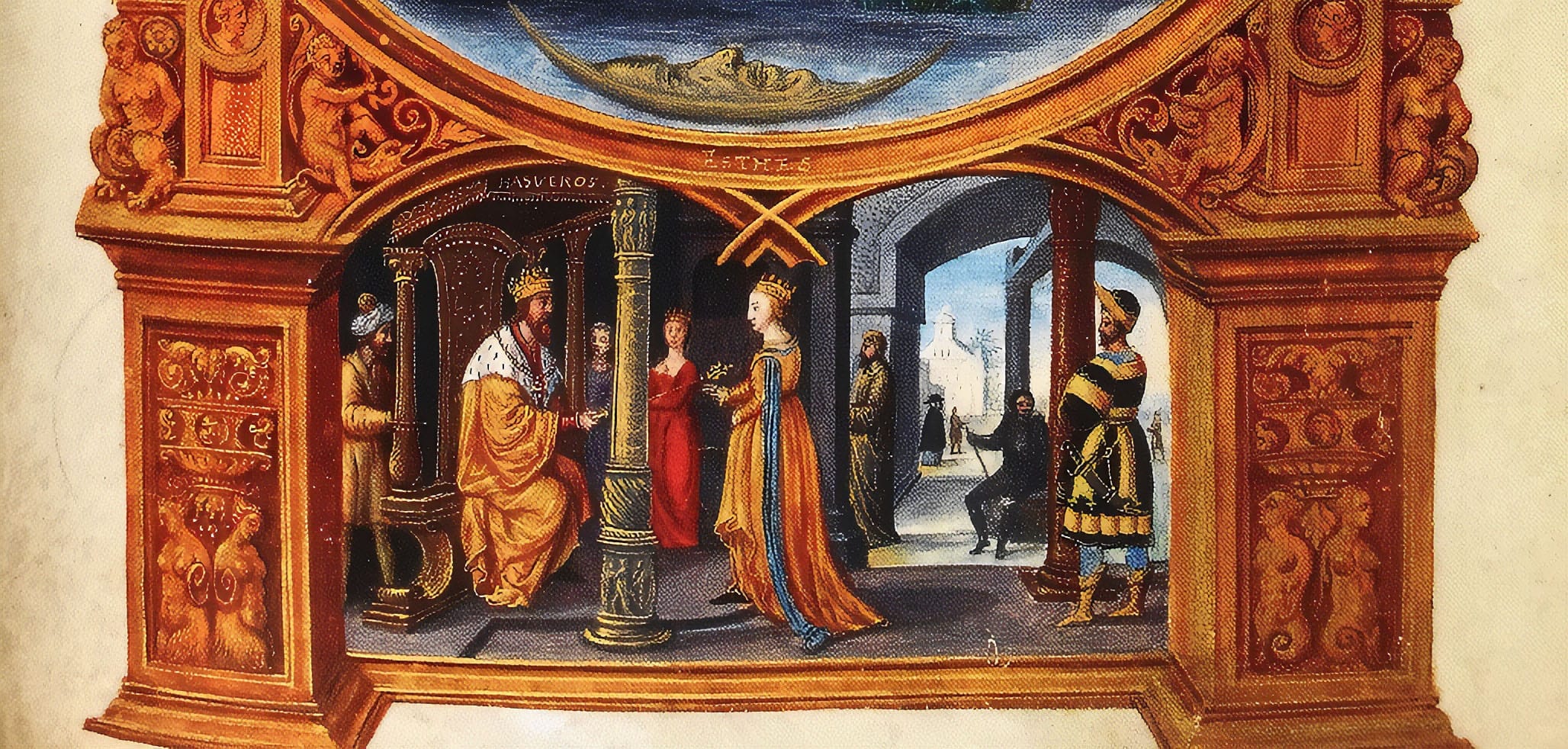

The next feature to catch our eye in Mining the Ore is the biblical episode at the base scene. Mistakenly identified by Skinner as Ruth, this portion of the plate reflects a famous story recorded in the Book of Esther wherein the queen saves the Jewish people from King Ahasuerus’ pogrom. In commemoration of this reversal, the Jewish festival of Purim was established, which, for all practical purposes, resembles nothing so much as a Semitic circus or carnival, replete with rowdy parades, encouraged drinking, harmless pranks, and especially clown costumes. Indeed, clowns have come to be somewhat characteristic of the Mardi Gras-like festivities. Something about them just seems to resonate with the queer quality of Purim. But, again, has any of this anything at all to do with magic mushrooms?

Regarding the relationship of clowns to fantastic fungi, Graham Hancock asks boldly in Supernatural:

“Were the visions of carnival-type figures seen by Strassman’s subjects, Maria Sabina, Michael Harner, and others influenced by strictly modern and culturally contingent television and circus spectaculars? Or is it possible that the direction of influence really flows the other way, and that the inspiration for the earliest clowns came from visions and hallucinations seen in altered states of consciousness – whether entered spontaneously or under the influence of DMT-linked hallucinogens? We know that at least as far back as ancient Greece, a land rich in psychoactive plants, stage plays, farces, and mimes frequently featured performances by dwarves and children dressed up in ways quite similar to modern circus buffoons. Before that, the history of such theatrical figures is obscure – as well it might be if they had emerged from occult realms that were originally accessible only in visions.”(5)

At first glance, Hancock’s speculations might seem ridiculous. But, when one considers the archaic nature of the impish trickster archetype to which the mushroom is tied – and the fact that even Jung admitted in a letter to a student that hallucinogens such as mescaline and LSD may induce a brush with what he termed the “collective unconscious,” Hancock’s pontifications suddenly appear not only excusable but warranted. As Terence McKenna once noted, “the archetype of DMT is the circus. These [entities]…at one level, they’re clowns.”[1]

Apropos Queen Esther, most scholars agree that the name Esther was derived from Ishtar, a Babylonian goddess of war and sex. Identified with the Mesopotamian goddess, Inanna, legend holds that Ishtar descended to Kur, the ancient Sumerian Underworld, passing through seven gates or arches, where she received the magical water of life – a reference which any 16th century Alchemist would immediately recognize as an allusion to the famed elixir vitae. Heinrich, of course, conflates this elixir with a tincture or brew prepared from magic mushrooms.

Remarkably, Ishtar’s consort, Tammuz, was a deity of grain and cow herders around whom an entire Eleusis-like mystery tradition was erected. (Note that one variety of magic mushroom, P. cubensis, grows only upon the dung of cows that have been fed with grain.) Tammuz is referenced directly in the Book of Ezekiel, where his female followers are described as “weeping” for his demise. According to British cultural anthropologist, E.S. Drower:

“The author of Ezekiel 8:17 rails against such abominations as the worship of Tammuz or the sun and those who ‘put the branch to their nose.’ This is interpreted by most OT authorities as a reference to Zoroastrian practices, where in the Haoma rite the priest holds the barsom in front of his face.”(7)

.

While the reference to the “branch to their nose” is indeed obscure, that Drower and others have linked this cryptic phrase to the Haoma rite of the Zoroastrians is especially significant. The Zoroastrian religion appropriated the ancient Soma rite of the Vedantists as Haoma, both of which have been connected to magic mushrooms in the past, most notably by R. Gordon Wasson in Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality and later by O.T. Oss and O.N. Oeric in their Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower’s Guide, where it is claimed by a pseudonymous Terence McKenna that, in 1984, heterodox Bengali Hindus announced the identification of Soma as “a psilocybian mushroom, Stropharia cubensis [now classified as Psilocybe cubensis].”(8)

Ishtar’s father, Sin or Nanna, too deserves some mention. McKenna wrote in his formidable treatise, Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge:

“In the mythologies of the Near East, there is a lunar god that must have been imported to India from the west. […] The patron deity of Harran was a male moon god: Sin or Nannar. He was thought to have arisen from a god of nomads and a protector of cattle related to the masculine cult of the moon god in early Arabia. His daughter Ishtar in time overshadowed all the other female deities, as did her counterpart Isis in Egypt.

As the father, or source, of the Goddess, it is fitting that Sin wears headgear suggestive of a mushroom. No other deity in the Babylonian pantheon has this headgear. I found three examples of Sin or Nannar on cylinder seals; in each the headgear was prominent, and in one instance the accompanying text by a nineteenth-century scholar mentioned that this headgear was in fact the identifier for the god.”(9)

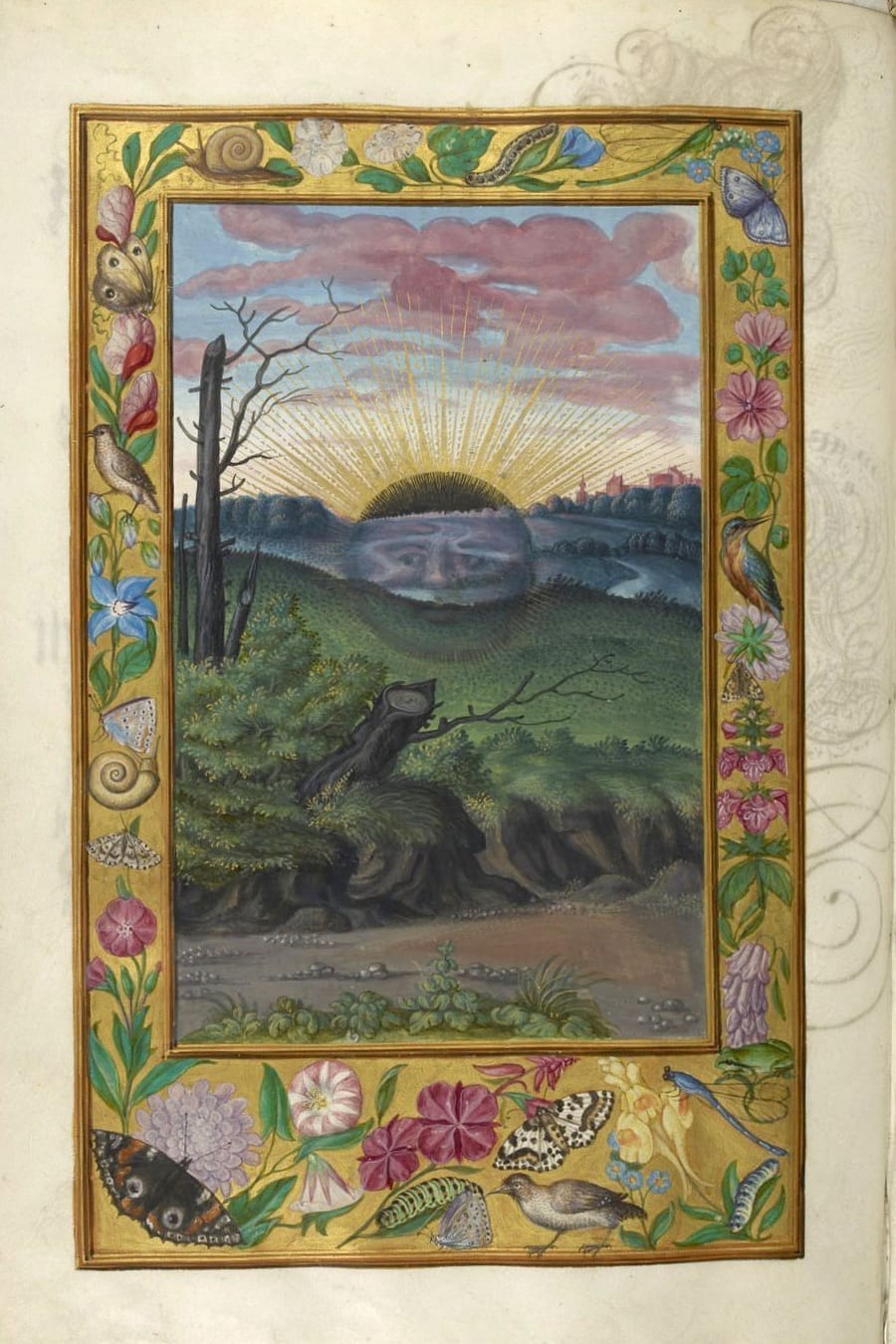

As McKenna makes clear, in addition to being loosely associated with fungi, Sin was a male moon god. Aside from a small number of instances among certain Native American tribes, masculine moon deities are an extreme rarity. Although, we can think of at least one other masculine lunar god who has already received mention in the present study: Soma. That’s right; not only was Soma a lunar deity, but he was a masculine one. Strikingly, if one directs his gaze immediately above the biblical scene at the base of the plate, in the pool of water directly below the busy miner duo, he may clearly see floating therein a crescent moon possessing the obvious face of a reposed male. Is this our Soma?

Splendor solis is indeed a curious tract, and plate 5 is perhaps the most curious of them all. The search for meaning in Alchemical manuscripts is a daunting, dizzying task that brings us “from swerve of shore to bend of bay,” against 16th century Germany all the way to the ancient Near and Far East. The mushroom model of interpretation outlined by Heinrich in ‘95 is to my knowledge one of the best devised for navigating the murky depths of Alchemical symbolism.

We hope that our short explication of a now obscure Alchemical plate has helped to demonstrate why we believe that to be true.

Written by P.D. Newman

Ask Terence McKenna. “The World and Its Double.” Accessed on Feb. 04, 2020.

Hancock, Graham. Supernatural: Meetings with the Ancient Teachers of Mankind. Disinformation. New York, NY. 2007.

Heinrich, Clark. Magic Mushrooms in Religion and Alchemy. Parkstreet Press. Rochester, VE. 2002.

McKenna, Terence. Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge. Bantam Books. New York, NY. 1993.

Oss, O.T. Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower’s Guide. Quick American Publishing. Oakland, CA. 1991.

Rush, John A. Entheogens and the Development of Culture. North Atlantic Books. Berkeley, CA. 2013.

Skinner, Stephen. Splendor Solis: The World’s Most Famous Alchemical Manuscript. Watkins. London. 2019.

Wasson, R. Gordon. Persephone’s Quest: Entheogens and the Origins of Religion. Yale University Press. New Haven and London. 1986.

1. Skinner

2. Wasson, p. 136

2b. Pers. Comm.

3. Ibid., p. 28

4. Heinrich, p. 175

5. Hancock, pp. 245-246

6. Ask Terence McKenna

7. Rush, p 261

8. Oss, p 77

9. McKenna, pp. 114-115