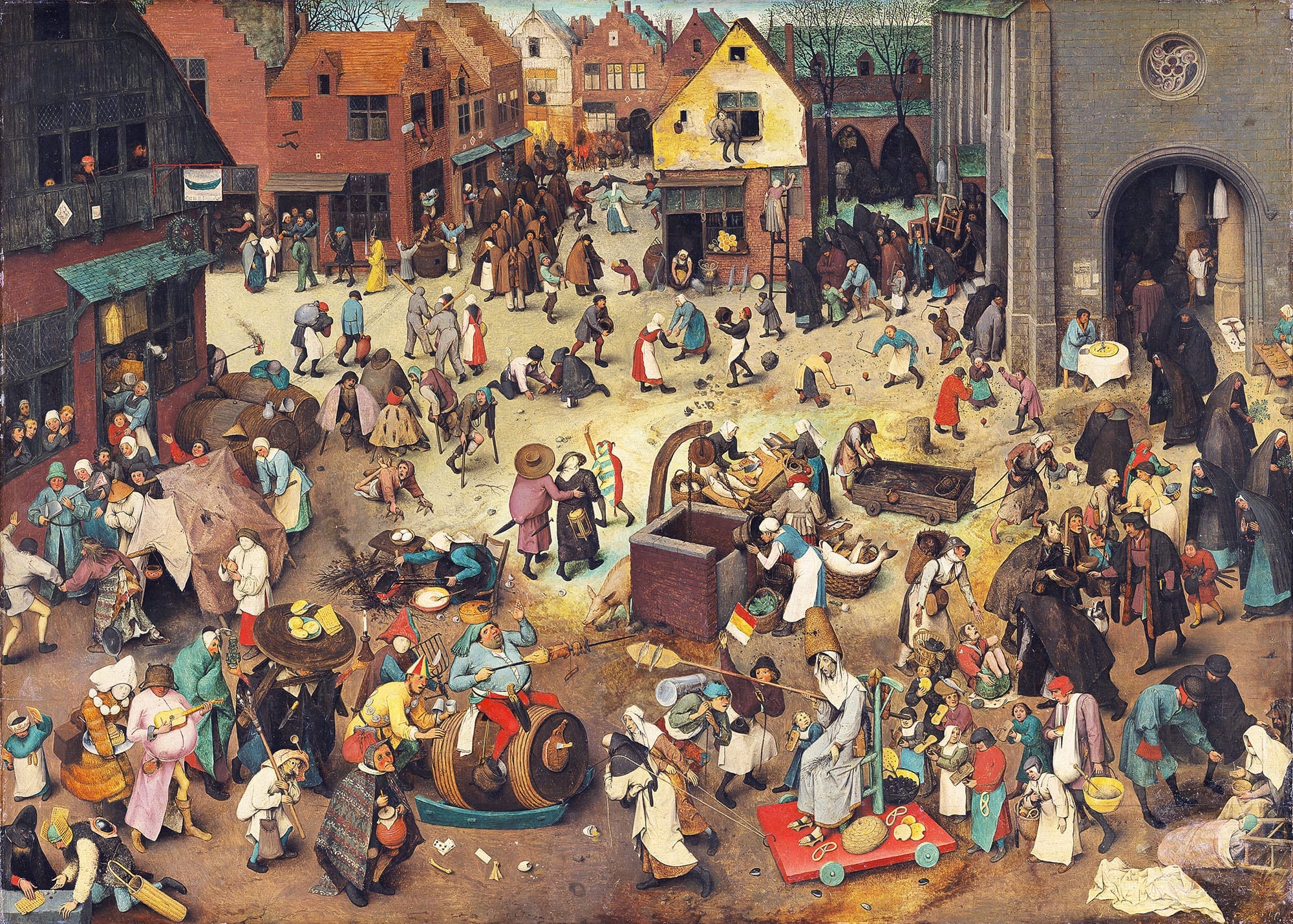

Main Image: The Fight Between Carnival and Lent, 1559, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Of Carnivals and Kings: Myth, Meaning, and Mischief in Mardi Gras

“Today I asked for a god to pour some wine in my eyes

Today I asked for someone to shake some salt on my life

Look! Everything’s spinnin’!”

– Faith No More, ‘King for a Day’

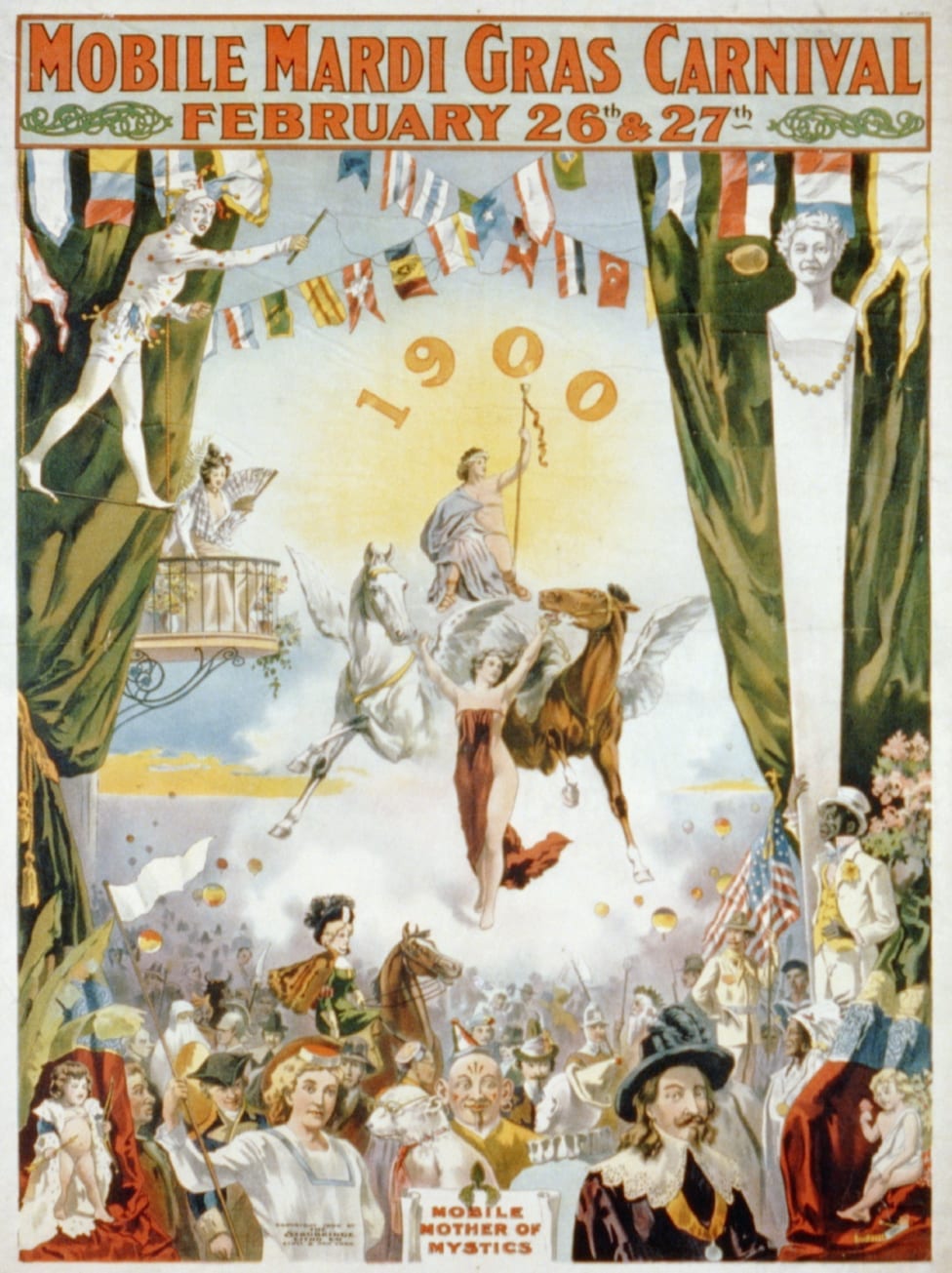

Neatly nestled within the Christian calendar, Carnival season begins Epiphany or Three Kings Day, on January 6, and ends Shrove Tuesday or Mardi Gras, “Fat Tuesday,” on February 16. During this time, mystic societies or krewes, as they’re often called, organize lavish parades and masquerade balls, often themed with mystical, magical, and mythological motifs, whose symbolism sometimes seems to betray a link with our ancient, forgotten roots.

It is clear that Carnival season is intended to function in two ways. Firstly, Carnival alludes the salvation offered all men, not only Jews, through the Christian savior’s martyrdom. Hence its beginning on the day of Epiphany, when three wise men or “Magi,” a pagan priesthood from Persia, were permitted to pay their respects to the infant Jesus. It is perhaps because of this accepted extension beyond the Judeo-Christian demographic that pagan elements have been allowed to playfully creep into the annual festivities.

Secondly, ending as it does the day before Ash Wednesday, the observance which kicks off Lent (the forty day period of fasting officially ending on Easter), Carnival season at its heart is essentially about indulgence, satiety, and excess. If, as one English poet pronounced, “the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom,” then Carnival season may well land us on wisdom’s very doorstep.

There is therefore, naturally, a subtle subversiveness to the celebrations. Not unlike the Jewish holiday of Purim, during Carnival, cultural and societal norms are surrealistically warped and turned on their heads. During Carnival,

“all the ordinary rules and hierarchies of society may be overturned. But it is not exactly chaos. It has an organizing principle, which is reversal, the world turned upside down. The most lowly are exalted and the exalted are brought low. Slaves become masters and masters become slaves. The bishop hands his miter over to a boy. Men become women and women become men. Carnival was when the king became a fool and a fool became a king.”

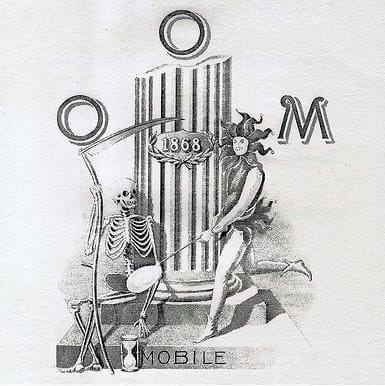

One example of reversal is the lavish, theatrical costumes adopted by the revelers. Another is the election of a Carnival ‘king for a day,’ a veritable “Lord of Misrule,” as his analogue was referred to in England.

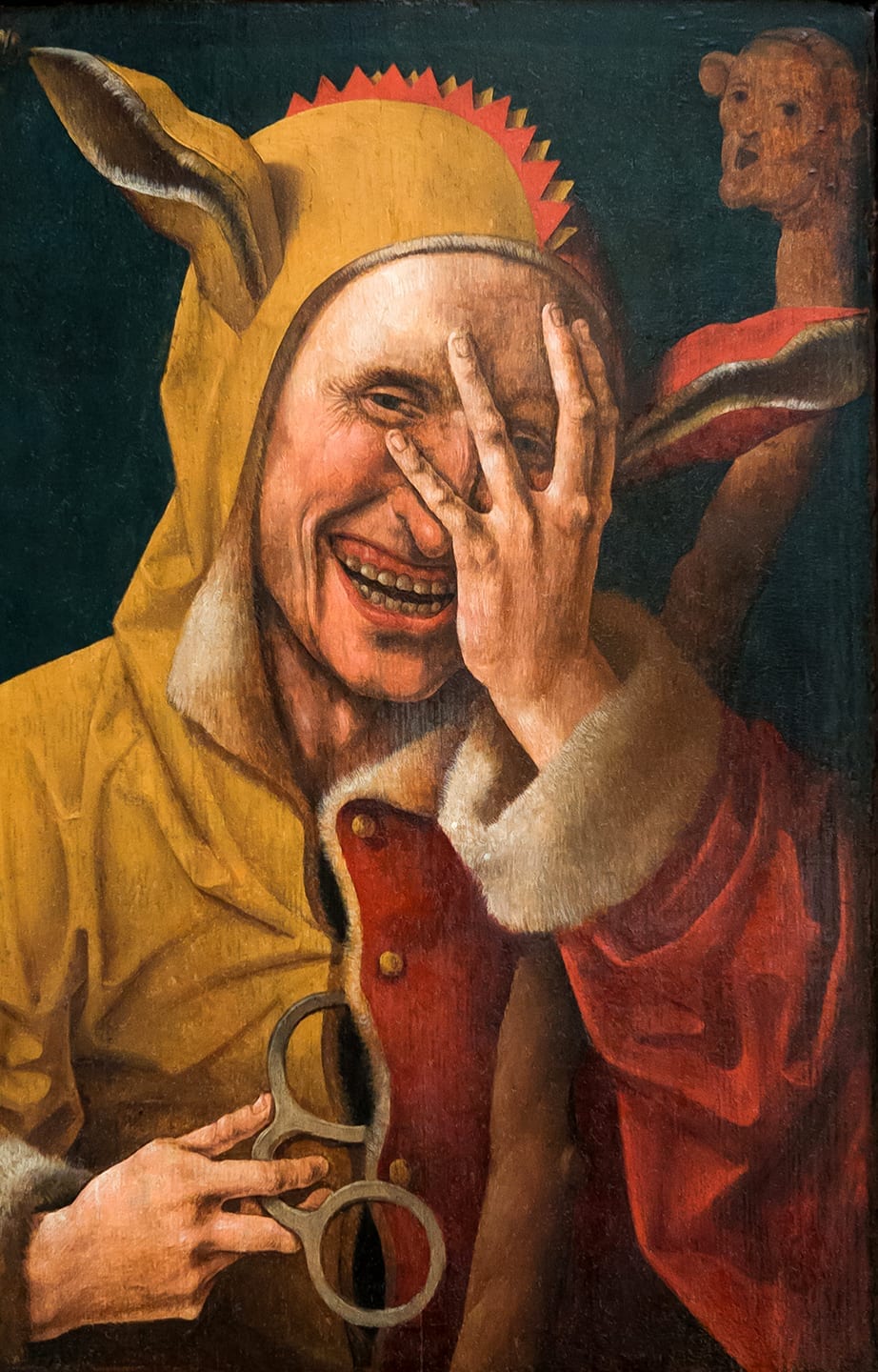

“There is a person in whom the essence of carnival is distilled – the Lord of Misrule, chosen by lottery every Christmas season in England, someone from the lower orders who is temporarily elevated, in the spirit of carnival. He is the architect of the carnival, whose responsibility it is to bring the overturning into effect again, year after year. For a timeless moment this nobody wields greater power than a duke, this pretend lord is a real lord, channeling the energies of sex and intoxication and dance. He is grotesque but beautiful. He is a clown, a fool, something that ordinary people would look on with scorn and condescension – […] He is a pantomime devil who may become a real devil.”

For a time, the Lord of Misrule was given all the control of an actual lord or king – almost. Echoing much of the lore presented in Sir J.G. Frazer’s magnanimous study of folk religion and magic, The Golden Bough, the (mis)rule of these carny caricature-kings would inevitably be cut short by the end of the festivities, thus returning the world to its fixed, tongue-in-groove pathways of daily repetition and blind habit. As Christians were crossed on the forehead with Palm Sunday frond ashes on Ash Wednesday the following morning, paying their visits the various Stations of the Cross at their local parish, already well into the abstinence their fasts, the surreal celebrations of Carnival season would fade into the background of everyday life in favor of the normal and commonplace. There, time somehow seemed to move more slowly, as though Carnival had really taken place on a mountaintop, where, as the community climbed higher and higher, the hours actually did race by faster and faster.

Similar celebrations can be traced at least as far back as ancient Rome where, between December 17 and December 23 of the Julian Calendar, the Saturnalia festival was held in honor of the Titanic temporal deity, Saturn-Kronos. Not unlike Carnival, during Saturnalia, social norms were systematically overturned as a “King of Saturnalia” was temporarily elected, chosen from among the common folk. Meanwhile, a Carnivalesque ‘beggar’s banquet’ or so-called “fool’s banquet” was prepared. Here, slaves and servants alike were cheerfully seated at tables alongside other unfortunates, where their everyday masters had to wait on their every whim, hand and foot. At the height of the festivities, a sacred bull was finally sacrificed in honor of the Roman deity.

Although, according to L. Craig Roberts, author of the charming book, Mardi Gras in Mobile, Carnival season may have its origin in an altogether different Greco-Roman festival: Lupercalia.

“Many present-day religious-based festivals started as pagan, or secular, celebrations. An early Egyptian celebration held during the month of February has been termed a primitive crop-growing festival. It is believed that five thousand years ago, this festival spread into what is now France. There the Druids held an early spring festival at which they sacrificed a young bull, which was called boeuf gras, meaning fatted calf. This festival was Fête du Soleil, or Festival of the Sun.

When the Romans conquered most of what is now Europe, they embraced an old Greek festival, calling it Lupercalia. This event was held every year on or about February 15 until the end of the fifth century. At this celebration, the tradition was to sacrifice a fatted ox. It was yet another late winter or early spring festival.

As the Romans accepted Christianity and over time formed the Roman Catholic Church, an attempt was made, in order to accelerate conversions, to change the old “fatted ox” celebration into a more Christian celebration connected to their season of Lent. Thus Carnival, as we know it, was born.”

Roberts goes on to explain that, etymologically, the word Carnival is a combination of the Latin caro, carn – “flesh,” and levare, “to put away.” Carnival might therefore be translated as ‘to abstain from meat.’ Hence the placement of Carnival prior to Lent, when meat, as opposed to the even more rare sweets, was willfully forgone. In a Nietzschean act of transvaluation, where there once was offered a “fatted” bull, the very eating of meat has now been translated into the sacrificial act.

During the early Middle Ages, these “late winter or early spring” observances engendered a number of rather bizarre and otherwise inexplicable ecclesiastical traditions. For example, in his essay, On the Psychology of the Trickster Figure, published in The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, C.G. Jung tells us of a number of odd customs.

“A report from the year 1198 says that at the Feast of the Circumcision in Notre Dame, Paris, ‘so many abominations and shameful deeds’ were committed that the holy place was desecrated ‘not only by smutty jokes, but even by the shedding of blood.’ In vain did Pope Innocent III inveigh against the ‘jests and madness that make the clergy a mockery,’ and the ‘shameless frenzy of their play-acting.’ Two hundred and fifty years later (March 12, 1444), a letter from the Theological Faculty of Paris to all the French bishops was still fulminating against these festivals, at which ‘even the priests and clerics elected an archbishop or a bishop or pope, and named him the Fools’ Pope (fatuorum papam). ‘In the very midst of divine service masqueraders with grotesque faces, disguised as women, lions, and mummers, performed their dances, sang indecent songs in the choir, ate their greasy food from a corner of the altar near the priest celebrating mass, got out their games of dice, burned a stinking incense made of old shoe leather, and ran and hopped about all over the church.’ […] In certain localities even the priests seem to have adhered to the ‘libertas decembrica,’ as the Fools’ Holiday was called, in spite (or perhaps because?) of the fact that the older level of consciousness could let itself rip on this happy occasion with all the wildness, wantonness, and irresponsibility of paganism.”

It’s difficult to imagine such shenanigans taking place inside the walls of a house of worship today. But, as the Swiss psychiatrist later makes clear, it took considerable effort and even more time for the church to tame these archaic, ecstatic customs and canalize them into something that, while certainly not Christian, weren’t so glaringly pagan – or, should I say, hermetic.

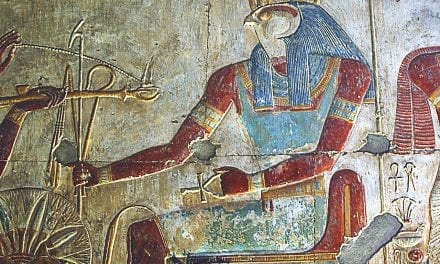

Within the French esoteric tradition of the 1920s, Carnival season, which was of course born in France, took on something of a hermetic, even alchemical significance. This is hardly surprising. Hermeticism was born out of the Hermetic corpus, a series of Egyptian-Greek wisdom texts dating to the 2nd century or earlier. Recall that Carnival season has possible roots in both the Egyptian “primitive crop-growing festival” cited by Roberts, as well as the ecstatic Saturnalia and Lupercalia festivals of ancient Greece and Rome.

In illustration of this latter interpretation of Carnival, we’ll end this synopsis with a quote from the mysterious French alchemist, Fulcanelli. For he and his circle, the various parades and masquerades of Carnival season became a veritable theater of the gods, presenting the eternal mystery play of existence in all of its weird and freakish wonder for all willing to surrender to the natural forces that lay in wait just behind the courteous, rational personae we wear for the world. Per Fulcanelli,

“There was the Feast of Fools – or of the Wise – a processional hermetic affair, which used to set out from the church with its pope, its dignitaries, its enthusiasts and its crowds, the common people of the Middle Ages, noisy, frolicsome, jocular, bursting with vitality, enthusiasm and spirit, and spread through the town. What a comedy it all was, with an ignorant clergy thus subjected to the authority of the disguised Science and crushed under the weight of undeniable superiority. Ah! the Feast of Fools, with its triumphal chariot of Bacchus, drawn by a male and a female centaur, naked as the god himself, and accompanied by the great Pan; an obscene carnival taking possession of a sacred building; nymphs and naiads emerging from the bath; gods of Olympus minus their clothes; Juno, Diana, Venus and Latona converging on a cathedral to hear Mass. And what a Mass! It was composed by the initiate Pierre de Corbeil, Archbishop of Sens, and modeled on a pagan rite. Here a congregation of the year 1020 uttered the bacchanal cry of joy: Evoe! Evoe! – and scholars in ecstasy replied:

Haec est clara dies clararum clara dierum!

Haec est festa dies festarum festa dierum!”