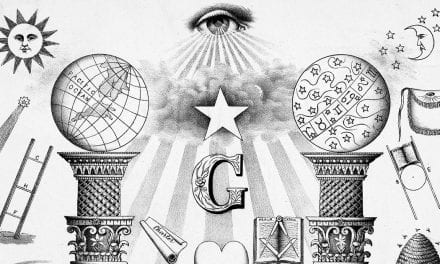

THE SYMBOLIC GEOGRAPHY OF THE LODGE

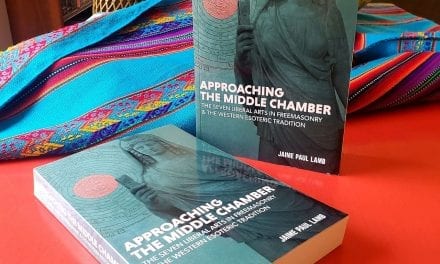

Excerpt from The Archetypal Temple

The following is a sample chapter from Jaime Paul Lamb’s new book The Archetypal Temple and Other Writings on Masonic Esotericism

Written by Jaime Paul Lamb

There is an interesting, though regrettably underdeveloped passage in Mackey’s Symbolism of Freemasonry likening the form of the lodge to the geography of the ancient known world. He begins by addressing the Masonic significance of the oblong square before offering the following observation…

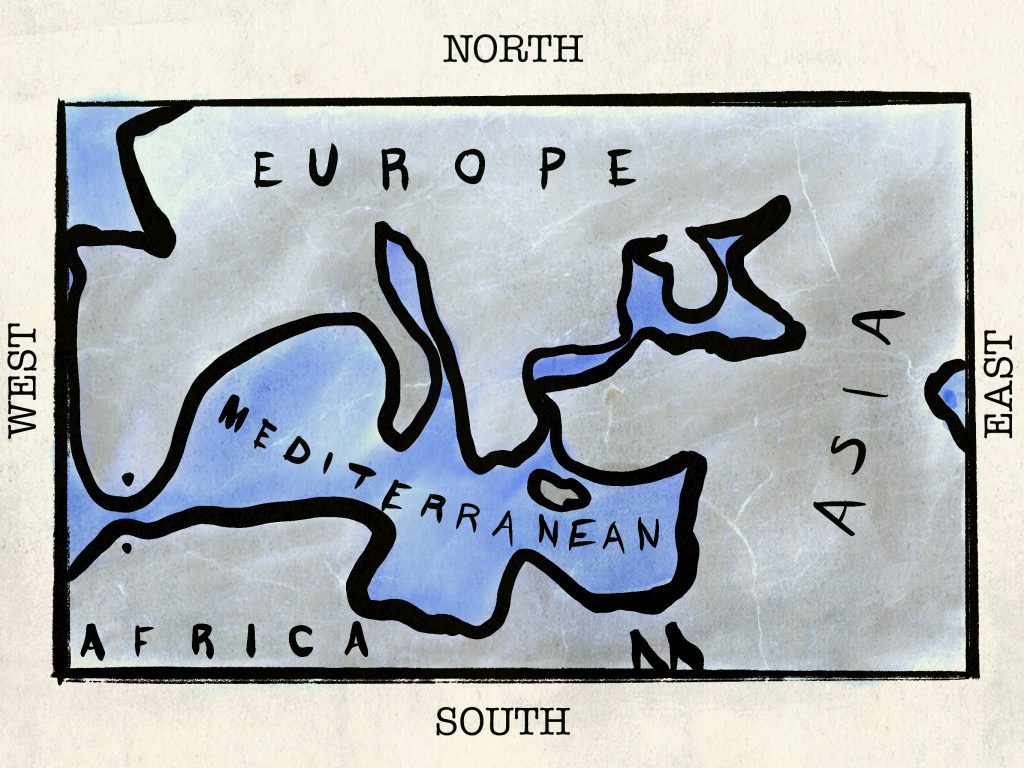

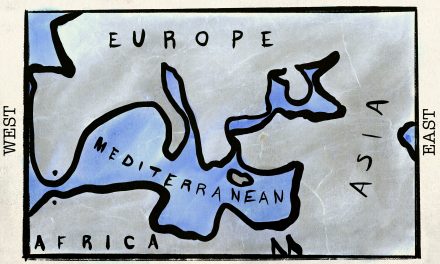

If, for instance, on a map of the world we should inscribe an oblong figure whose boundary lines would circumscribe and include just that portion which was known to be inhabited in the days of Solomon, these lines running a short distance north and south of the Mediterranean Sea, and extending from Spain in the west to Asia Minor in the east, would form an oblong square, including the southern shore of Europe, the northern shore of Africa, and the western district of Asia, the length of the parallelogram being about sixty degrees from east to west, and its breadth being about twenty degrees from north to south. This oblong square, thus enclosing the whole of what was then supposed to be the habitable globe, would precisely represent what is symbolically said to be the form of the lodge, while the Pillars of Hercules in the west, on each side of the straits of Gades and Gibraltar, might appropriately be referred to the two pillars that stood on the porch of the temple. [Mackey. The Symbolism of Freemasonry. “The Form of the Lodge.” New York: Clark and Maynard. 1882. pp. 102-103]

After superimposing the Brazen Pillars on the porch of King Solomon’s Temple over the Western Mediterranean’s Pillars of Hercules, Mackey abruptly stops short of applying this perspective to other features of the lodge. In the present essay, we will pick up the thread begun by Mackey and endeavor to flesh out the symbolic geography of the lodge.

First we note that Mackey’s oblong square essentially centers on the Mediterranean Sea. The word Mediterranean conjoins the Latin medius (meaning “middle”) and terra (meaning “land” or “earth”), and most directly comes to us from the Latin mediterraneus, denoting the sea “in the middle of the earth.” If the Mediterranean Sea may be thought of as the center of the world, as it anciently was in the region, then we may understand the lodge as being a microcosmic model of the known world.

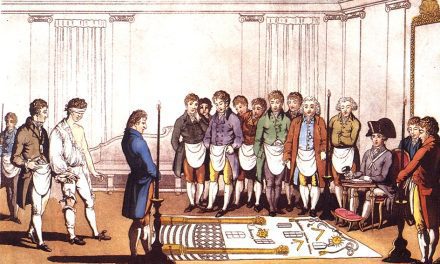

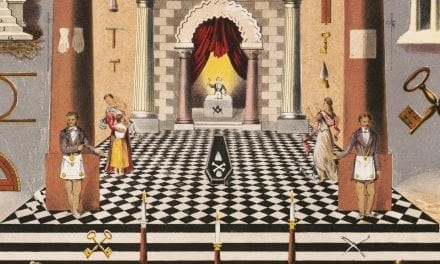

Mackey orients us in this regard by his superimposition of the pillars at the “West Gate” of both the sea and the lodge – Morocco’s Jebel Musa to the south and Spain’s Rock of Gibraltar to the north corresponding to J∴ to the south and B∴ in the north of the lodge. Thus, we know that the directionality of the lodge is aligned with that of the ancient world – an oblong square whose longer sides run east-to-west. From here, we may begin to fit other geographic features to the lodge and, conversely, other features of the lodge to the geography of the ancient world.

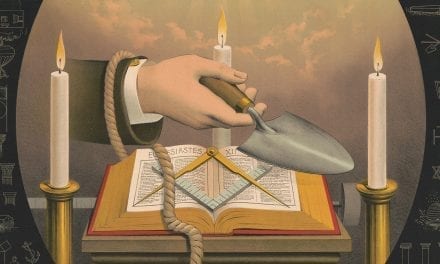

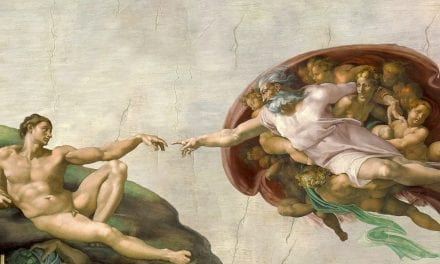

Obviously, the Levant plays an important geographical role in Masonic ritual and symbolism, as the region contains both Jerusalem, the site of King Solomon’s Temple, and the Phoenician city of Tyre, from whence King Hiram and Hiram Abiff hailed. The easternmost end of the lodge corresponds to the Levant in this symbolic geography, which is appropriate since this is where the Worshipful Master is seated as well as being the source of Masonic Light.

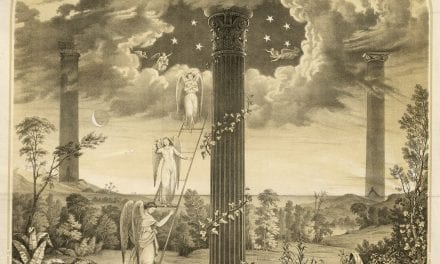

The island of Crete is the largest of the Greek islands and is relatively centrally located in the Mediterranean Sea. The Minoan civilization flourished on the island during a precessional period known as the Taurian Age, which is the approximately 2,000-year period when the zodiacal sign of Taurus hosted the vernal equinox. Consequently, there was an abundance of Taurian symbolism in Minoan culture, such as the minotaur, the practice of bull-leaping and numerous frescoes depicting the animal. This is masonically significant, since the Fraternity’s Anno Lucis (“Year of Light”) marks the approximate commencement of this precessional age. [For more on this interpretation, see: Lamb. Myth, Magick & Masonry. “Section II: Solar and Astrological Symbolism in Freemasonry.” The Laudable Pursuit. 2018] Thus, it would make sense, symbolically, for the island of Crete to represent the altar in the geographical lodge, since this is the place where Masons are brought to Light.

In Masonic symbolism, the north is considered the “place of darkness”; this makes sense in the geographical model as well, since the Sun will always have a lower declination at higher, northern latitudes. Oppositely, the south is the station of the Junior Warden and is represented geographically by North Africa – a correspondence which seems to imply a resonance between the Legend of the G∴M∴H∴A∴ and the Osirian cycle wherein the murdered god becomes entangled in the acacia tree at Byblos.

This perspective of symbolic geography not only allows us to view Masonic ritual and symbolism from the mythological perspective of the ancient world, but also to view the ancient world through the lens of Freemasonry. Both superimpositions of meaning seem to support the other in strangely resonant ways, which seems to imply that there may be some species of occult synergy at work, or perhaps that Masonic symbolism is just another iteration of an ever-recurring mythological projection.